Introduction

The issue of shrinking cities has been on the rise in the past, and it creates serious problems around the globe (Stansel, 2011). This problem of shrinking cities is common amongst cities in developed countries like the United States and Europe among others even though it can happen in the developing world (Rieniets, 2009). Currently, Europe is experiencing severe cases of urban shrinkage occasioned by the population decline, which stands at 40 percent in most cities (Turok & Mykhnenko, 2007; Kabisch & Haase, 2011). According to Haase et al. (2014), different terms like abandonment, decay, urban crisis, decline, disubanisation, demographic change, and blight among others have been used to define occurrences related to shrinkage. Martinez-Fernandez et al. (2016) note that even though the terms “shrinking cities” and “urban decline” are related, they describe different phenomena. On one side, urban decline is a localised and occasional problem associated with modern urban development and planning, and it can be solved through strategic planning. On the other side, shrinking cities is an international and national planning problem occasioned by the growth of capitalism in the 21st century. According to Haase (2013), urban shrinkage is the monolithic population decline in cities due to varied factors including political regime changes, socio-economic, environmental, or financial elements, and settlement patterns among others. The phenomenon is a social and economic process involving the use of space and land in a given city (Berg et al. 1982; Lever 1993; Garreau 1991). Moreover, Wiechmann (2007) notes that any urban centre with over 10,000 residents and it has been facing depopulation for over two years together with undergoing economic changes characterised by structural crises can be termed as a shrinking city.

According to Schett (2011) and Deng and Ma (2015), city shrinkage is subject to socio-economic, structural, political, and natural factors coupled with demographic changes. These factors work in concert to create the shrinkage phenomenon. As shown in Figure 2 below, city shrinkage occurs due to diverse but highly interconnected processes, which work together to cause the problem. Rink et al. (2010) posit that even though the decline of population in a given area is a function of macro-processes like socio-economic, political, or natural factors, it heralds other micro-process issues like brain drain, underutilised or abandoned infrastructures, unoccupied houses, and aging among others.

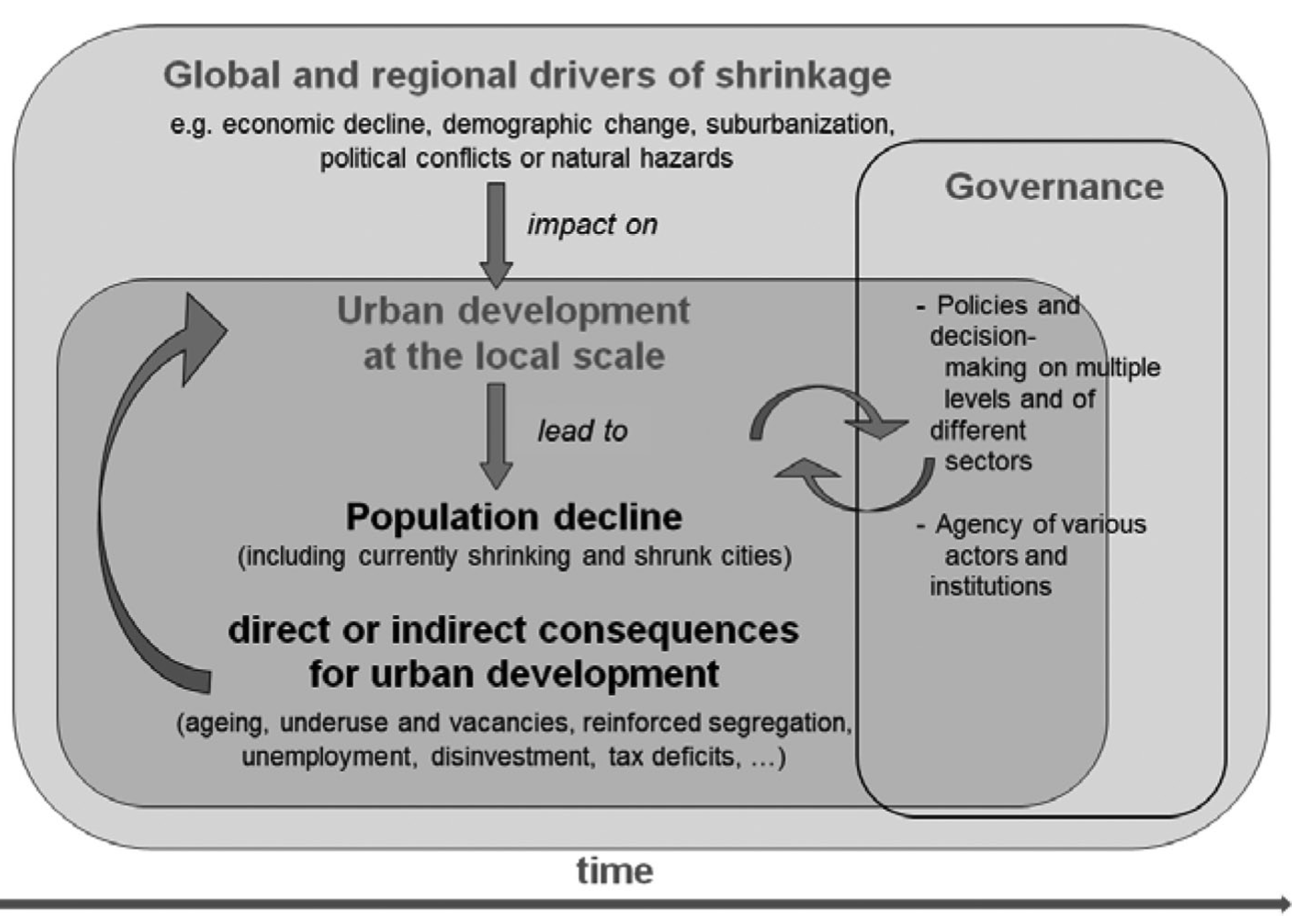

The heuristic model by Haase et al. (2014) puts the shrinkage issue under the conceptual and historical context by covering the causes, effects, receptions, and feedback circuits together with highlighting how these aspects interact. As shown in Figure 3, the heuristic model identifies the global and regional factors that contribute significantly to the shrinkage phenomenon. According to Haase et al. (2014), this model does not consider the multileveled nature of governance responses and feedback circuits, but it can play a critical role when trying to connect and compare the shrinkage issue in different contexts. Besides, Stansel (2011) established a strong correlation between growth and taxes. In this light, shrinking cities like Buffalo, Syracuse, and Detroit in the US should address the issue by alleviating the tax burden and cutting down expenditure as a way of restoring growth patterns.

The problem of urban shrinkage affects different areas like infrastructure, housing, businesses, and employment. Other affected areas include the growth of land-use perforation, social separatism, and cohesion, the financing of municipal activities, and the creation of residential and commercial brownfield (Oswalt and Rieniets 2006; Großmann et al. 2008; Haase et al. 2010; Lauf et al. 2012). Additionally, with shrinkage, the quality of urban life deteriorates due to the unoccupied houses and land on top of reconfigured land-use patterns (Haase, 2008). Moreover, the availability of more space with diminishing occupants disrupts the demand-supply patterns in a city as shown in Figure 4 below (Elmqvist et al. 2013).

However, several studies have been conducted to show that urban shrinkage can be used to provide improved ecosystem services (European Commission, 2015; Elmqvist et al. 2013), thus, leading to the rebirth of the affected urban centres (Kabisch et al., 2009). In the light of this understanding, Deng and Ma (2015) maintain that the unoccupied urban land may point to an economic decline, but from an optimistic perspective, it can be used to provide important ecosystem services.

Couch et al. (2011) agree that addressing the problem of shrinkage is complicated; however, Verwest (2011) holds that governance responses to the problem fall into two categories. In the first category, policymakers acknowledge the shrinkage problem, but they ignore it and adopt growth-oriented policies. In other cases, the shrinkage problem is dealt with proactively by converting the abandoned spaces into green areas, which improve the quality of urban life. In the second category, policymakers focus on policies that determine the best places for investment in areas affected by population decline especially inner cities and those with high growth potential like suburbs.

On the same issue of responses, Bernt et al. (2012) note that the issue can be categorised into to two. The first category involves Western holistic explicit growth or stabilisation endeavours that focus on addressing the effects of shrinkage. The second category is a post-socialist approach where the focus is on growth strategies to create job opportunities occasioned by inward investment and funding from different quarters without necessarily thinking of the aftermaths of the shrinkage problem. The first category seeks to address the problems related with shrinkage by understanding the causes. On the other side, the second category endeavours to combat such problems reactively without any attempts to understand the causes.

Heritage and Historic Environment

The World Heritage Convention (1972), which is recognised globally as a legal tool in the conservation of heritage, defines the terms “cultural heritage” and “natural heritage” in Article 1 and Article 2 respectively. The definition of cultural heritage includes physical elements like buildings, monuments, or sites that add ecumenical value from a historical or scientific perspective. However, natural heritage covers all natural areas that add worldwide value from scientific and conservation perspectives based on their geological, biological, or physical attributes. Besides, LeBlanc (1993) deconstructs the term ‘heritage’ to include anything that people, whether separately or collectively, endeavour to conserve for the coming generations. Based on this understanding, LeBlanc (1993) maintains that constituents of heritage go beyond the conventional thinking to include a wide array of factors. However, the concept of heritage narrows down to few selected things probably due to the preservation costs involved in the process.

The English Heritage (2014) explains the limitations of heritage, which fall into ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ versions. In the ‘official’ heritage, objects/sites are identified using an established criterion, which then restricts the definition to some areas nationally or internationally. In other words, the ‘official’ version of heritage adopts a top-down approach where public institutions are involved in the identification process. On the other hand, the ‘unofficial’ version is a bottom-up approach where locals identify places and objects based on their relationships and experience. According to the Getty Conservation Institute (2002), the values of heritage and historic environment are made up of three significant factors namely economic, environmental, and cultural values. Besides, Ching Fu (2016) posits that such values can fall into tangible and intangible categories. The varied forms of values are attributed to the view that heritage can be divided into physical and nonphysical versions with each playing a key role in social coherence, creativeness, and innovativeness in any given setup (UNESCO, 2013). Apparently, individuals are concerned with the value that landscapes add to the cultural heritage together with the natural attributes to form a functional ecosystem (Natural England, 2009).

Ismagilova et al. (2015) experimented with the issue of historical heritage in the context of socio-economic development in Eastern Europe and came up with the following observation. A person’s cultural understanding underscores the need for studying heritage in historical and cultural contexts. These contexts are subject to the people’s understanding of religion, history, and traditional practices, which then determine the relationship that individuals develop with objects and sites (Ismagilova et al. 2015). Besides, Ismagilova et al. (2015) posit that cultural and historical heritages can be grouped into six different forms based on their predominant signs. The six forms include historical, cultural, archaeological, religious, ethnographic, and ecological/natural resources.

Heritage Impacts

The following sections explore how heritage affects people and places.

Economic Impact

The heritage of a given place plays a central role in the socio-economic and cultural endeavours. Therefore, most countries exploit the heritage role as an asset in the involved cities to foster economic development (Ismagilova et al., 2015). Besides, historical heritage attracts tourists, and this aspect can be used to create employment and foster business growth in a given area (English Heritage, 2014). In other words, the economic advantages of heritage can be realised by practicing tourism based on heritage (English Heritage, 2014). For example, such kind of tourism in the UK amounts to £14 billion in economic output, and it creates over 390,000 employment opportunities (Oxford Economics, 2013). Besides, heritage-based tourism boosts local economic developments from different spheres (English Heritage, 2010). According to the HLF (2010), for every £1 gained from heritage visits, 32 percent goes to site fees while 68 percent goes to local businesses that provide different goods and services. Moreover, over 50 percent of employment opportunities created by heritage-based tourism are off site (English Heritage, 2010).

Additionally, heritage can support a certain area from two perspectives. First, the residential property values increase directly due to the demand for housing facilities, which also guarantees appreciating value in the future. Second, the impact can be indirect due to the need for the associated public service, which leads to more people moving to such areas (Coffin, 1989; Leichenko et al., 2001). Moreover, given that designated historic areas lead to improved property values, shrinking neighbourhoods can be revived and restored in the process (Leichenko et al., 2001). However, Smith (1998) and Wojno (1991) warn that such designation can have negative impacts as some individuals may be displaced in the process of creating a historical environment.

The concerted efforts to preserve heritage have direct positive impacts on the value of properties coupled with the strengthening of the social cohesiveness in the affected districts. This growth can have spill over effects to the neighbouring areas, which also experience an upsurge in property values together with economic development (Rypkema, 1994; Listokin et al., 1998; Coulson & Leichenko, 2001). Therefore, based on this understanding, it suffices to conclude that the preservation of heritage goes beyond the superficial protection of historical sites to act as a way of economic development and community preservation (Leichenko et al., 2001). However, Schaeffer and Millerick (1991) caution that the demarcation of historic districts may affect property values negatively based on the terms and conditions imposed on accessing and using such sites.

Impact on Place

The places hosting objects of heritage experience positive impacts in terms of identity. Heritage becomes valuable due to the contribution that it gives to the identity of a given place. In other words, by visiting a certain historical or natural heritage site, individuals gain understanding, and they develop personally. People learn from history, and heritage covers this area of learning, which shapes the identity of a certain place. Besides, heritage sites become famous due to their uniqueness, which is part of their identity (Ginting & Wahid, 2015). For instance, Christians in England associate with the Temple Church in Bristol because it contributes to the understanding of their religious beliefs. This way, the identity of this historical heritage grows, which fosters its attractiveness to most Christians interested in knowing the history of the church in England. Besides, when such areas become famous, the residents are proud to be associated with the fame, thus, developing a strong sense of place (English Heritage, 2009). Mori (2009) released a report on how the public develops attitudes on beauty based on given attractive places. In the report, 70 percent of the respondents noted that they would love to be associated with or live in areas with historical value. Notably, 87 percent agreed that heritage improves the quality of life in the affected areas (Mori, 2009). Additionally, the investments that come with the preservation of heritage increase the sense of place. According to the English Heritage (2010), over 90 percent of residents in such places noted that after such investments, their pride was boosted, which elevated the sense of place coupled with improved social interactions.

Community and Individual Impacts (Educational impact and Personal development)

At the individual level, people derive pleasure and gain knowledge from historical and natural heritages, which lead to improved health and wellbeing. According to the Heritage Lottery (2013), individuals benefit from heritage by experiencing personal development in terms of gaining new skills or experiences, which leads to improved confidence, new perspectives, and knowledge. Moreover, the English Heritage (2014) holds that young people can develop useful skills by visiting and interacting with the local heritage sites. Besides, the social capital and mutual understanding occasioned by strengthened social fabric are important impacts of heritage on communities and individuals (English Heritage, 2014). In a study by BOP Consulting (2011), around 90% of HLF volunteers were beneficiaries of heritage projects, which improved their social wellbeing.

Impact on Regeneration and development

English Heritage (2014) indicates that the numerous investment drives geared towards the preservation of heritage denote regeneration and development impacts on the historical environment. In this light, every £1 invested in a historical site leads to additional 60% economic activity over a period of a decade, which translates into £1.6. Additionally, businesses with high potential for growth come up in areas with historical importance (HLF, 2013). One of the critical aspects that determine the success of a business is location. According to English Heritage (2014), most business owners concur that historical environments are as important as access to good infrastructure like roads when deciding the location of a business. Conventionally, businesses located in listed buildings generate higher Gross Added Value (GAV) as compared to their counterparts in other places. Therefore, historical and cultural heritage lead to regeneration and development in the process of identifying valuable past and present objects, which are used to model a desired end in the future (Ismagilova et al. 2015).

Middle Eastern context

The definition of Middle East as a geographical location varies based on different aspects. For instance, from the start of the 20th Century, the term “Middle East” was taken to mean a geographical area that lies between Russia and India according to Alfred Mahan, who is a US naval officer and a lecturer (Adelson, 1995). In another instance, AlSayyad and Tureli (2009) define the Middle East to include Palestine, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Egypt, and parts of Northern Africa. Besides, different scholars and historians have defined Middle Eastern cities using varied terms like the Arab Cities, the Oriental Cities, or the Islamic cities, and at times the Ottoman Cities. While some of the cities in this region were redefined during the Ottoman civilisation, some were expanded or merged during the colonisation process (Kramer, 1997). Some scholars see colonisation as an external force that shaped and remodelled the Middle Eastern cities (Malik, 2001; Home, 1997; Al-Sayyad, 1992). The next section explores the history of the modern Middle Eastern cities together with the challenges facing nations in the region.

Historic overview

According to Kamrava (2013), scholars approach the Middle Eastern history from two distinct eras, viz. the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods. However, the evolution of the Middle East can be viewed from five broad epochs (Cleveland and Bunton, 2013; Gelvin, 2011). The first period comes between the 7th and the 18th Centuries whereby the region hosted some of the earliest human civilisations. During this period, most civilisations had undergone the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (Kamrava, 2013). However, this period was marked by a decline in the size, number, and perhaps importance of most Middle Eastern cities especially from the 16th century. This trend persisted until the start of the 20th Century (Tessler, 19940). The second period runs from the start of the 19th Century to around 1918, when the First World War ended. The 19th Century was eventful for the Middle East following the entry of the Ottoman Empire and the occupation of Britain and France. During this period, the region underwent significant socioeconomic, political, and cultural changes (Khater, 2011; Cleveland and Bunton, 2013:231; Khalidi, 2007). Apparently, colonialism played a central role in the shaping of the Middle East (Kamrava, 2013).

Most researchers and scholars have marked the 19th Century as the rebirth of the modern Middle East (Gelvin, 2011). Krammer (1997) adds that starting from the 19th Century, the Middle Eastern cities have undergone different modernisation phases. Westernisation, which heralded capitalism, private land ownership, and modern government practices, influenced the development of the Middle Eastern cities and especially Aden, Damascus, and the Gulf cities (Yarwood, 2011). For instance, capitalism ensured that cities were build to achieve an economic end while modern government structures introduced planning. Consequently, these trends shaped the identities of the Middle Eastern countries by minimising regionalism and promoting globalisation.

The third period covers the period between the end of the First World War and 1945 when the Second World War ended. This period was characterised by the struggle for independence from the colonialists. The fourth period runs from 1945 to the 1970s when the region experienced the emergence of independent states following the exit of colonial masters from Europe (Gelvin, 2011). Finally, the last period runs from the 1970s to the start of the 21st Century, which is characterised with uprisings and rebirth. The construction industry experienced unparalleled growth during this period. The growth was occasioned by the increased demand for crude oil in the international market, which promoted exports from the Middle East (Al-Hathloul, 2004). According to Cleveland and Bunton, (2013), over 50% of the global crude oil reserves are in the Middle East and specifically the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, and Kuwait. Given the economic significance occasioned by the presence of crude oil coupled with strategic geographical location, some of the oldest Middle Eastern cities have formed and shaped the significance of the region (Madbouly, 2009; Gelvin, 2011). However, the region has suffered numerous setback and negative publicity due to the numerous occurrences including the ongoing Arab-Israel conflict, the Iran-Iraq conflict, the Gulf War, and the Lebanese Civil War among others (Kramer, 1997; Gelvin, 2011).

Key Challenges

Some of the major challenges facing countries in the Middle East include increased urbanisation rates, water scarcity, acts of God, and climate change (World Bank, 2014). Therefore, strategists and researchers emphasise the need for key reforms in administration as a way of solving long-term problems in the region (Yarwood, 2011; Garba, 2004; Al-Hathloul, 2004). The rate of urbanisation in the Middle East presents a complex phenomenon, just like other places in the developing world. The complexity occurs due to the structure and functionality of the linkage patterns across the region (Eben Saleh, 2004). The region’s geographical setup has influenced the population patterns including dispersion, density, and settlements (Kamrava, 2013). The Middle East has experienced exponential population growth in the past, which compounds the rural-urban migration, thus, complicating the issue of urbanisation in cities in this region (Madbouly, 2009). The Word Bank (2014) revealed that over 62 percent of the Middle East population resides in the urban areas, and this number is expected to rise by at least 45 percent in the next 15 years. For instance, the Saudi Arabian population growth has overtaken the country’s GDP (Larrabee, 2006) and the majority of the people live in urban centres. This problem has caused structural and planning challenges in urban centres, which has led to the emergence of informal settlements (Madbouly, 2009).

Therefore, governments in this region face the growing challenge of providing the citizens with the basic needs, because the population keeps on growing at a rate that economic development cannot match (Madbouly, 2009). Besides, the exponential population growth has led to unemployment rates in the region (Cammett et al., 2015). Ironically, countries in the Middle East have the over 50% of crude oil reserves, but the unemployment problem has not been addressed (Madbouly, 2009; Cammett et al. 2015). For instance, Egypt is currently undergoing one of the worst economic periods in its history due to the recent uprisings, which have seen the dethronement and sentencing of two incumbent presidents. Consequently, the country has experienced capital flight acceleration, reduced Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and negative economic growth (Cammett et al. 2015). Consequently, unemployment rates have soared in the past few years since the start of the Arab uprising in 2010. Therefore, the country needs the creation of over 500,000 job opportunities annually to normalise the situation. The challenge of unemployment cuts across the region and it will take concerted efforts from the key players to address the problem (International Labour Organisation, 2002). Unfortunately, governments in these regions lack the political will to address such challenges while the private sector may not have the capacity to create enough annual job opportunities (Cammett et al., 2015). Therefore, the governments should create a friendly environment for investors coupled with giving tax incentives to create the required annual job opportunities in the region.

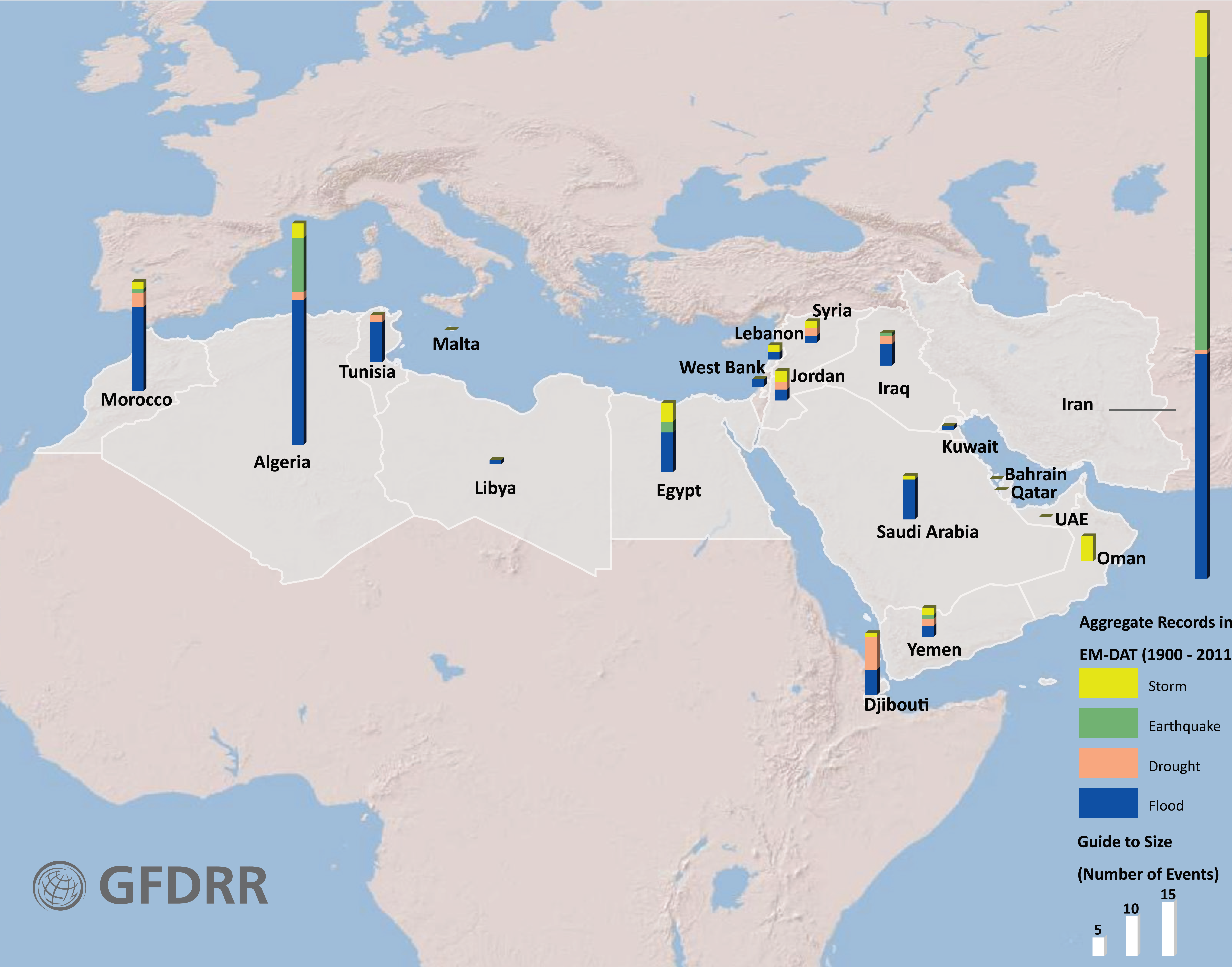

The rising urban populations have compounded the severe water shortage problem in the Middle Eastern cities. Besides, the majority of these countries lie in deserts, which underscores the water shortage issue (Choguill, 2008). According to Madbouly (2009), the accessibility of water in the region is below the international standards as paltry 1.4 percent of the global freshwater is found in this region. Moreover, 80 percent of the 1.4 percent is found in Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, which deepens the challenge of managing the scarce resource in the face of surging population growth (Madbouly, 2009). Acts of God also form part of the problems ailing the Middle East. The common natural disasters in the region include floods, earthquakes, storms, and droughts as shown in Figure 5 below. Even in countries like Yemen and Lebanon where disaster management units have been created, the functionality of such initiatives is impeded due to technical and financial constraints or poor governance (World Bank, 2014). However, chaos and political instability are the greatest challenges facing countries in the Middle East. According to Madbouly (2009), without peace and political stability, the other challenges facing the Middle East may not be addressed effectively. Political upheavals have impeded economic and socio-cultural advancement. For instance, the ongoing Syrian conflict has left the country on the brink of collapse with destruction and devastation being the only products of the War.

The number of refugees is astronomical, cities have been destroyed, families have been exterminated, and the government is destabilised (Cammett et al. 2015). Such conflicts at times spill over to the neighbouring countries, which scuttles any development efforts in the region. For instance, the Iran-Iraq War and the Lebanese Civil War affected the stability of the region significantly (Kamrava, 2013). Additionally, the majority of the leaders in the region are despotic, which leads to uprisings that destabilise the Middle East further. For instance, Egypt, Syria, and Yemen have suffered greatly from these political upheavals (Cammett et al. 2015). Such instabilities have led to astronomical poverty levels across the Middle East. By the start of the 21st Century, over 20% of the population in the Middle East survived on less than 2 dollars a day (Madbouly, 2009). The number has increased following the political upheavals. Such poverty levels in the face of other problems addressed earlier strain the available resources. Therefore, governments are overwhelmed to provide the necessities and decent infrastructural developments in the cities and across the countries (Madbouly, 2009). Finally, the problem of informal settlements and slums is on the rise given the increasing population and the lack of infrastructural development to match such growth. Therefore, the emergence of informal settlements and slums has been inevitable in some countries in the region like Egypt, Iran, and Yemen Madbouly, 2009). These countries need to come up with slum-upgrading plans and policies to address the problem of informal settlements in the long-term (Madbouly, 2009). The policies should address the ever-increasing cost of land, escalating housing prices, and poor public land management among other issues in the region.

Urban Planning and Governance

After the Second World War, planning has been a major challenge in most Middle Eastern countries (Hartog, 1999). Therefore, government agencies have come up with comprehensive long-term plans to address the problems. Some of the plans seek to promote the national strategies and policies on spatial development and management. The majority of the policies are geared towards the creation of streamlined urban areas characterised by efficiency through strategies that promote the physical stock of capital and encourage public-private partnerships in the development and maintenance of infrastructure by lowering production costs through tax rebates among other initiatives (Eben Saleh, 2004).

In the Middle East, cities are constructed based on central municipal government guidelines (Alskait, 1998), which creates some uniformity due to the centralised planning systems (Alskait, 2000). The planning exercise is hierarchical, and it adopts a top-down approach, thus, excluding the participation of all the stakeholders. The top-down approach is one of the problems facing urban planning in the Middle East (Choguill, 2008). This centralised nature of planning leads to critical urban planning problems including ineffectualness, inefficiency, and the lack of feedback from the stakeholders, which limits the process’ improvement (Alskait, 2000:22; Mandeli, 2015). In the light of this understanding, it suffices to conclude that the immediate way of streamlining planning in the Middle Eastern countries is through decentralisation (Choguill, 2008; Alskait, 1998). The decentralisation process will ensure that all stakeholders are involved in decision-making by giving their opinions and feedback (Alskait, 2000). Going forward, the future of planning in this region will depend on the extent that the policymakers will focus on sustainable development and participatory decision-making from all the stakeholders (Eben Saleh, 2004). Besides, the involved parties should think holistically, proactively, and futuristically as a way of formulating long-term strategies to address the current and future macro urban challenges in planning (Al-Hathloul, 2004).