Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a mental disorder that affects women as most of them have challenges speaking about the issue. Various researchers have investigated the issue and how it varies between first-time and non-first-time moms. They have also investigated the effect of breastfeeding on reducing the level of PPD. The findings have shown heterogeneous outcomes in various researches. The current study investigates whether first-time moms are more likely to get PPD than non-first-time moms. Furthermore, it examines if long-term breastfeeding is essential in reducing PPD. The research uses purposive sampling, where 151 participants are selected to participate in the research study. The participants are grouped into four age categories, below 18 years, 19-25, 26-39, and 40 and above. The measures used include the Edinburgh scale, demographic measures, and other mood and depression measures. The analytical tool used was a self-reported questionnaire consisting of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, demographic questions, and other questions. The descriptive statistics and t-tests show that first-time moms have high levels of PPD than non-first-time moms. Furthermore, ANOVA results show a significant mean difference between the breastfeeding groups implying that women who breastfeed for a long period have low PPD than their counterparts. First-time moms experience significant challenges that affect their mental development and performance, making them prone to PPD.

Postpartum depression, also known as PPD, is a silent disorder that women are afraid to complain about. It has direct effects on public health. Symptoms include anxiety, forgetfulness, helplessness, fatigue, and feelings of hopelessness. (Alomar, 2015). In developed nations, PPD is believed to affect 10 percent of women, but in developing countries, the effects are higher (Figueiredo et al., 2014). This is mainly among the low-income families in these regions as they usually have financial constraints. In places such as India, giving birth to a girl is a significant depressive factor as society’s expectation is based on the one giving birth to the male child (Alomar, 2022). Studies over time show that PPD can have long-term effects on the child’s development and growth as well as an attachment with the mother. In the long run, this also influences the mother’s mental health. According to Silverman et al. (2017), PPD is a non-obstetric complication common in most women and is linked with childbearing. It has a significant impact on the mother as well as the child since the period after birth greatly determine the infant’s development.

Various risks are associated with the PPD, such as the history of depression, age of the mother, complications during the pregnancy, obstetric factors, and other demographic characteristics. Pregnant women who are depressed have a higher chance of experiencing PPD. Moreover, women who used to have a history of depression before becoming pregnant or during that period have a high chance of experiencing PPD (Abdollahi & Zarghami, 2018). Education is also a critical factor as it helps one understand certain things, which lowers the effects of getting depression. PPD is highly experienced during the first six months, and this brings about the need for early diagnosis to ensure that it does not lead to adverse health effects (Alomar, 2022). The consequences affect both the mother and the child leading to a lack of mother-to-child bond, weakness, low school performance, malnutrition, delay in childhood development, insomnia, and child behavioral problems. Various researches show that PPD has a significant impact on the child and the mother with physical and mental problems.

PPD has a significant impact on women as it leads to the development of the comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and other effects such as anxiety. Pope and Mazmanian (2016) research shows that women diagnosed with PPD also tend to have effects of anxiety as well as obsessive-compulsive symptoms. PPD has different effects, such as self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and thoughts of harming the infant. The findings of this research support Alomar’s (2015) results by showing that women experiencing PPD have long-term negative outcomes. The effects include negative emotions, social problems, problematic cognitive development, and physical development problems. Pope and Mazmanian (2016) also show that the children of women experiencing PPD face a significant challenge in their physical and mental development. The research adds the effect of PPD among the parents with psychosis as it leads to infanticide (Pope & Mazmanian, 2016). PPD among individuals suffering from psychosis has adverse effects on the infant, parent, and family.

PPD in psychotic individuals leads to significant functional impairment and hospitalization. Silverman et al. (2017) utilized a longitudinal study model to investigate the factors that lead to increased PPD among women. Their findings suggest that PPD is high among women that had a history of depression than in women without depression history. The research shows that obstetric problems and maternal and perinatal factors are also associated with high PPD. Furthermore, their findings also show that first-time mothers and other women with subsequent children have different experiences with the PPD.

Maternal Age, First-Time Mom and PPD

Various researchers investigate the relationship between maternal age and PPD. The researchers are based on most pregnancy among adolescents is usually among first-time moms. Silverman et al. (2017) portray that maternal age is a significant predictor of PPD. Additionally, the effect of age is enhanced when individuals have a history of depression. Young women with a history of depression have a higher probability of getting PPD than their counterparts without a depression history. The effects of adolescent pregnancy are high because of the challenges that young mothers face. Most adolescents have less information regarding child care, which makes them not understand their development and the child’s development.

Understanding the responsibility, one has to the child is mediated by experience and age. The effect of age is also promoted by the possibility of the mother having received the diagnosis of depression (Holopainen & Hakulinen, 2019). Young mothers have less information regarding possible interventions that help curb depression. Similarly, first-time mothers also have the same problem, making it challenging not to have a depression history. Moreover, the chances of not getting a diagnosis are higher when experiencing PPD. Silverman et al. (2017) also show that women under 35 years also have an increased risk of getting PPD than those aged 25 to 29. The effects of depression extend to later ages, such as 30 to 34 and 35 to 39. First-time moms experience a significant life transition that affects their mental performance (Leahy-Warren et al., 2011; Smorti et al., 2019). The change is long-term and requires support to prevent mental pressure.

Breastfeeding and Postpartum

Previously, the breastfeeding and PPD relationship was perceived to be unidirectional. It was believed that PPD led to lower rates of breastfeeding. Currently, research shows that the relationship between the two is bidirectional, implying that PPD may lower breastfeeding; mothers who do not engage in breastfeeding tend to develop PPD (Pope & Mazmanian, 2016). Furthermore, other researches show that breastfeeding helps protect women from PPD and aid recovery among those that have PPD. Breastfeeding has a significant impact on both the mother and the infant. Beyond the nutritional outcomes, it has psychological benefits for the mother and the infants. It is essential in that it enables the creation of the bond between the mother and the child. The oxytocin hormones released during breastfeeding promote maternal bonding. This lowers the effect of the mother developing psychiatric disorders (Rivi et al., 2020). Additionally, breastfeeding is essential in regulating daily processes such as sleep and wake-up patterns for the infant and the mother (Wilson, 2018). This promotes mental wellness for both the mother and the infant.

Mothers who breastfeed are reported to have developed a positive mood with less anxiety. The infant and the mother benefit through enhanced immunity, nutritional value, emotional and cognitive development (Rivi et al., 2020). The biological benefits include antibodies that protect the infant from various childhood pathologies and deter the growth of the viral population in the gut (Hamdan & Tamim, 2012). Breastfeeding benefits the mother by lowering the chances of not getting ovarian cancer, blood pressure reduction, and weight loss. However, according to Borra et al. (2014), breastfeeding requires constant contact between the mother and the infant, which becomes a significant challenge for women with perinatal mental disorders. Women who are depressed have a low breastfeeding self-efficacy, thereby breastfeeding for a short period.

Despite women with depression having a problem with breastfeeding, it does not necessarily mean that breastfeeding has a positive effect on lowering the anxiety and depression symptoms. This is because there are women who do not have intentions of breastfeeding during this period and later decide to breastfeed their babies (Borra et al., 2014). It resulted in positive effects as they were able to have reduced levels of anxiety. Mothers that do not engage in breastfeeding despite not having a history of breastfeeding have a higher chance of developing PPD (Borra et al., 2014). McIntyre et al. (2018) support the assertion that breastfeeding is vital in reducing the PPD. McIntyre et al. (2018) argue that breastfeeding results in psychological consequences in women who had planned not breastfeed despite not having previous depression history (Borra et al., 2014). This shows the heterogeneous outcome of breastfeeding on the mental health of women. Women with early signs of PPD who have engaged in breastfeeding may have reduced PPD or not.

Aim of the Study

The aim of this study is to determine the relationship between breastfeeding & Postpartum depression and whether a first-time mum is more prone to be diagnosed with PPD than those who previously had babies.

Objectives

The objectives of the study are as follows; first, to identify the relationship between PPD and various mediators. Second, to identify whether variation in motherhood and breastfeeding affect the development of PPD.

Research Question

The research utilizes two research questions, first, do women who do not breastfeeds more likely to get PPD than those who breastfeed? And second, are first-time mums more likely to get PPD than those who have previously had babies?

Hypothesis 1

H1: First-time moms are more likely to get PPD than non-first-time moms

H0: First-time moms are not likely to get PPD compared to non- first-time moms

Hypothesis 2

H1: women who breastfeed for a long time have reduced PPD

H0: Women who breastfeed for a short period or not at all have reduced PPD

Methodology

Participants

The research utilizes a total of 151 participants; the inclusion criteria entail only women, and they form 100% of the participant in the study. The exclusion criteria are women who have not given birth because the study of PPD focuses only on first-time moms and women who have had more than one childbirth. Out of 151 participants, 148 are from the United Arab Emirates, while the two are from Bahrain. The participant age was grouped into four groups; the first group was 18 years and below, the second group was 19 to 25, the third group was 26 to 39, and the fourth group was 40 and above. The researcher uses a non-probability sampling method to select the population used in the research. This method is significant as it enables the researcher to select a specific population intentionally on the basis that it answers the research question (Klar & Leeper, 2019). Additionally, it is crucial to enable the researcher to estimate the resources, time, and costs needed to accomplish the research.

This research uses the technique of purposive sampling to select first-time mothers as well as other mothers. However, the challenge of this method is in choosing the number of participants to ensure that the data saturation objective is attained. The participants were recruited online through social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. These methods of recruitment were preferred because physical contact is not permissible due to COVID-19 pandemic effects. Participants were evaluated to ensure that they qualified to participate in the survey. During the recruitment process, it was made clear that the survey is not compulsory and one is free to participate or not.

Study Design

The research uses a quantitative research design to investigate the relationship between the PPD among first-time moms and other women that have had subsequent births. In this design, two main methods are used, which include descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics entails the calculation of mean, variance, and standard deviation. The inferential statistic entails using a T-test to identify the relationship between the two groups under study (Sykes et al., 2017). ANOVA is used to determine whether there is a variation in the mean among the breastfeeding group. Using a quantitative research design in this study is important because it enables the researchers to generate findings supported by statistics.

Measures

Various measures have been used in this research that are helpful in data collection. First, depression measures used involved questions administered by Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. The measure in this scale checks the level of depression among the study participants by evaluating their general feelings within the last seven days. Other attitude and mood measures were incorporated to check the levels of PPD. These measures include personal attitudes, disappointments, and annoyance. The effects of having a baby or babies among the participants were also measured by the fear that the mother has regarding their infants. This measure is essential in providing more information regarding the effects that women with babies have as a result of conceiving. The measure of insomnia was also included in the research. These measures provide a clear understanding of how depression affects various groups of women. Anxiety measures were used to help understand the levels of anxiety between first-time moms and other women. The measure of age is incorporated in the research study to provide information on the age brackets of the participants. Employment and age measures act as a mediator between the two groups. A breastfeeding measure is used to investigate the effects of breastfeeding on the PPD. Other mediating measures included in the self-reported questionnaire include the place of origin and marital status.

Procedure

The project was approved by the professor, and the researcher created a Google form survey that was used to collect data. The form was designed such that it had both English and Arabic. The link was provided to the qualified personnel, which was sent via email. The participants were advised to read the consent form in the first section of the questionnaire, which provided brief information regarding the study being conducted. The consent familiarized the participant with information on free participation at one’s will to enable those that are not able to participate the chance to not continue with the study. Additionally, the consent made it clear that individuals are free to continue or not at any point in the research. It also provided the importance of accomplishing the survey. The second section contained Edinburgh postnatal depression scale that the participants were expected to fill.

Analytical Tool

A self-reported questionnaire consisting of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale was the primary analytical tool used in this research. The scale contains ten screening questions that help understand depression symptoms among women before and after childbirth. The participant fills out the questionnaire, and the outcome is calculated based on the parent’s score. Individuals with a score less than eight show that they are not likely to have depression. Those with a score between 10-11 imply that they have possible signs of depression, between 12 and 13 show that individuals have a fairly high depression and above 14 indicates high depression. The second section of the survey had ten questions from the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale to identify if participants are at risk for PPD. There are 33 other questions about how they feel after giving birth. Finally, the last section consisted of 6 demographic questions: age, marital status, breastfeeding, and employment status.

Results

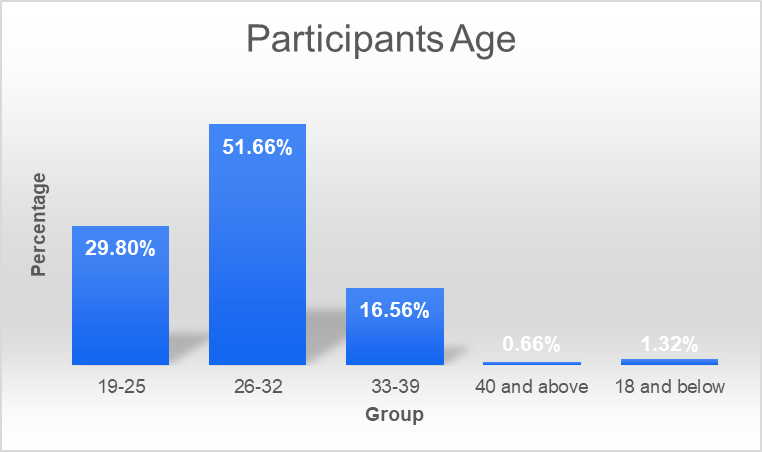

The participants were grouped into 5 age groups as shown in the table below.

The age group, 26-32, had the highest number representing 51.66% of the total participants. The age group, 19-25, is second with 29.80%, followed by 33-39 with 16.56%, the fourth group is 18 and below with 1.32%, and the last group is 40 and above with 0.56%. Figure 1.0 below shows the percentage composition.

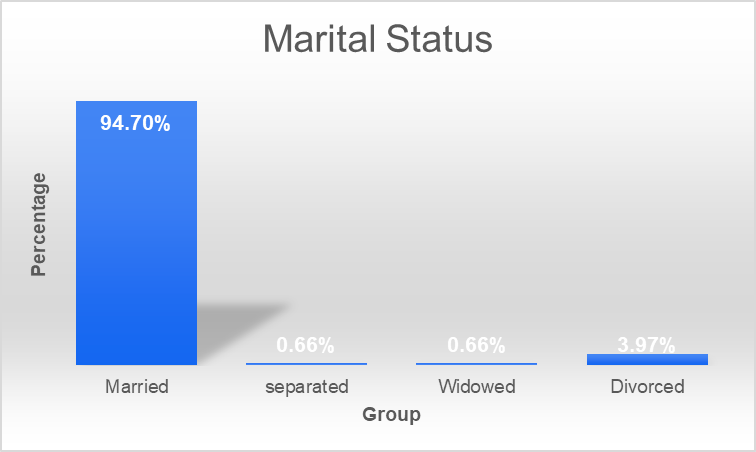

Marital status was included as a mediator between the PPD, first-time moms, and non-first time moms. Married women constituted the highest number of participants, with 94.70%. Divorced was second with 3.97%, followed by separated at 1%, and widowed with 1%. Table 3.0 and figure 3.0 below show the number of individuals and percentage composition, respectively.

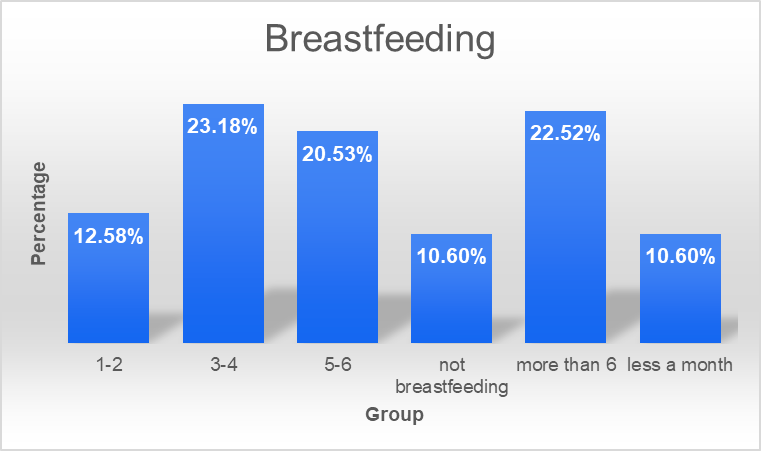

The participants reported the level of breastfeeding depending on the period. Most women reported breastfeeding between 3-4 months (23.18%). The second group is more than 6 months (22.52%), followed by 5-6 months (20.53%). The fourth group is 1-2 months (12.58%), followed by not breastfeeding and less than a month with 10.60%. These data are shown in table 4.0 and figure 4.0 below.

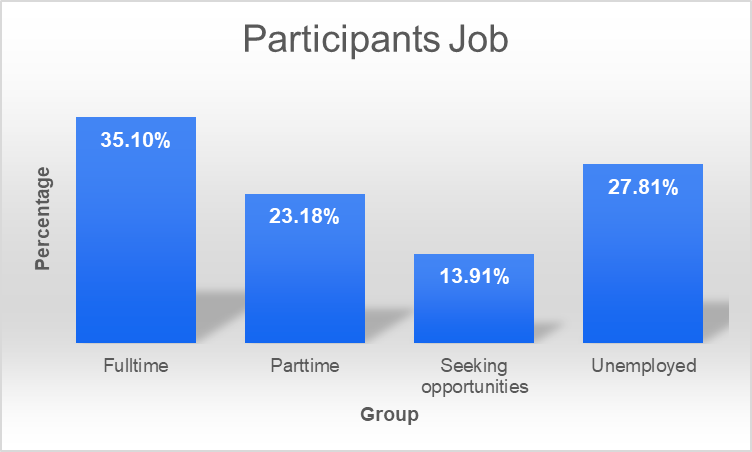

The participants’ employment status shows that most are employed (35.10%). The second group is unemployed (27.81%), followed by part-time (23.18%), and lastly, those seeking opportunities (13.91%). Table 5.0 and figure 5.0 below show the above statistics.

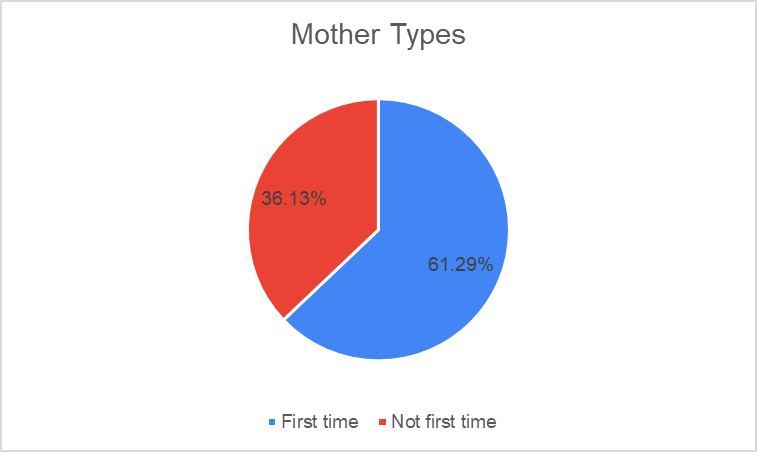

The composition of first-time moms (61.29%) was higher than non-first moms (36.13%). Table 6.0 figure 6.0 below shows the above statistics.

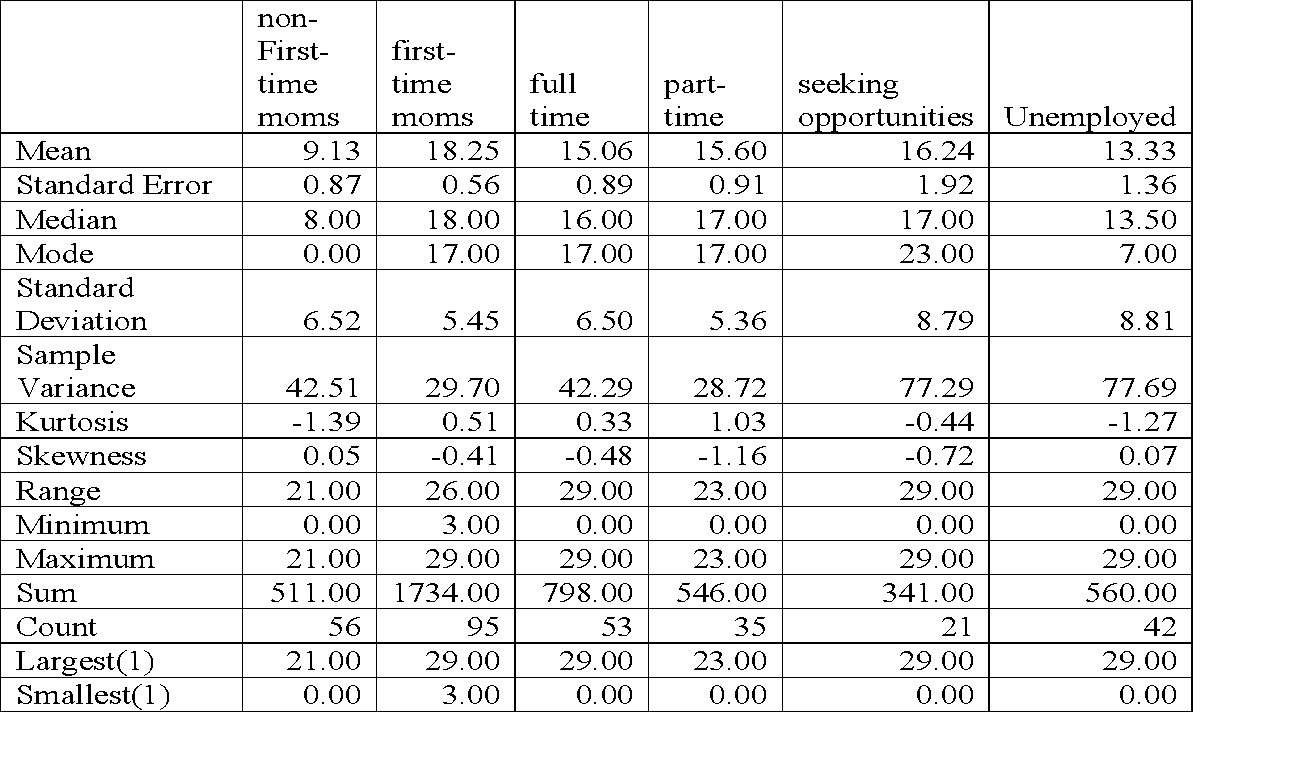

The PPD among the first time mom is higher (M =18.25, SD = 5.45) compared to non-first time moms (M = 9.13, SD = 6.52). Individuals seeking opportunities reported higher PPD (M =16.24, SD = 8.79). They were followed by part-time (M = 15.60, SD = 5.36), full time (M = 15.06, SD = 6.50), and unemployed (M = 13.33, SD =8.81). Above data is shown in table 7.0 below

Table 7.0: Descriptive statistics on PPD Score for the type of mothers and their employment status

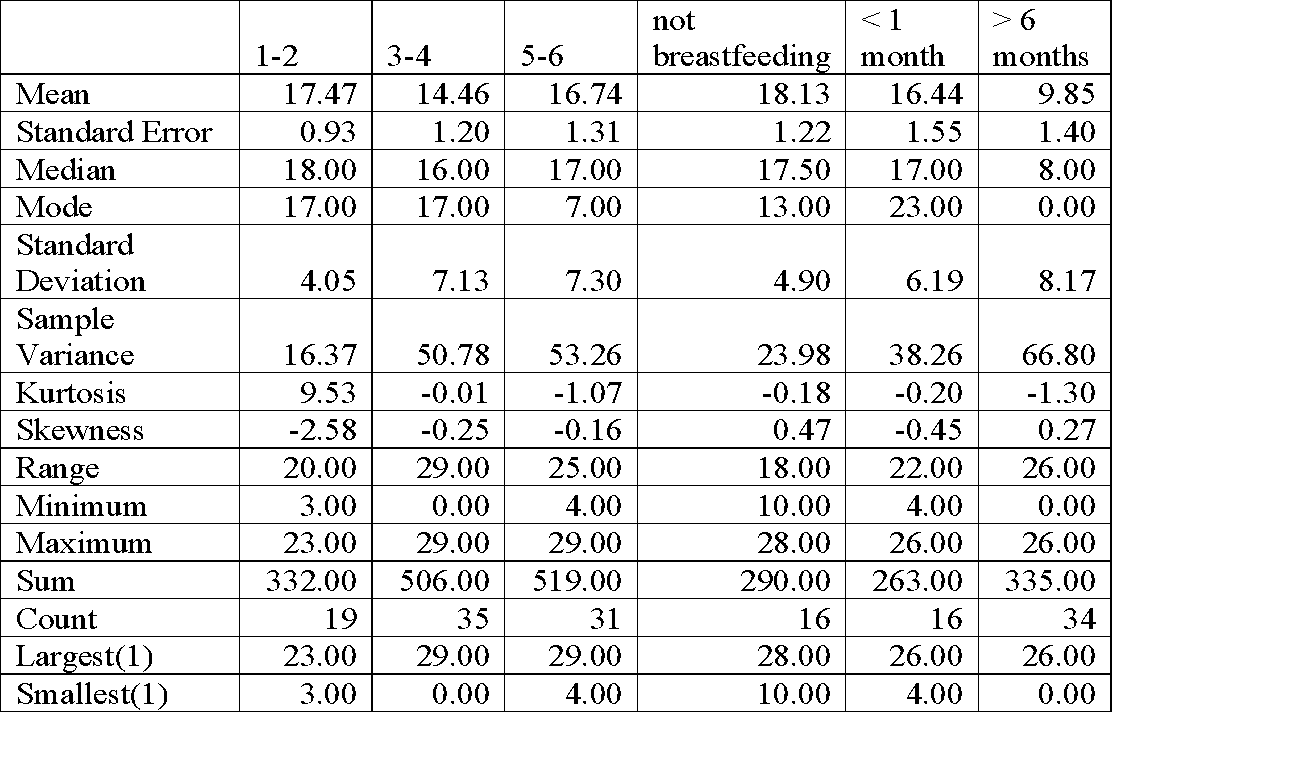

Women who do not engage in breastfeeding had the highest PPD score (M = 18.13, SD =4.90) despite having the least number of participants. They were followed by 1-2 months (M = 17.47, SD = 4.05), 5-6 months (M = 16.74, SD = 7.30), less than one month (M = 16.44, SD = 6.19), and 3-4 months (M =14.46, SD = 7.13). Women who breast feed more than 6 months did not show the signs of PPD as they have a low score (M = 9.85, SD = 8.17). The above statistics is shown in table 8.0 below.

Table 8.0: Descriptive on PPD score for breastfeeding

Women 18 years and below portrayed a high level of PPD (M = 16.50, SD = 3.54). They were followed by 19-25 (M =16.33, SD =6.42), and 26-32 (M = 15.42, SD = 7.41). Age group 33-39 have the lowest score of PPD (M = 10.96, SD = 7.41). 40 and above was only one woman who had no sign of PPD. The above statistics are shown in table 9.0 below.

The t-test results show that first-time moms experience a higher level of PPD than non-first-time moms, t (149) = -9.23, p < 0.01. This is portrayed in table 10.0 below.

One-way ANOVA results show a significant mean difference between the groups, F (5, 145) = 5.61, p < 0.01. This is illustrated in table 11.0 below.

Table 11.0: one-way ANOVA

Discussion

The descriptive statistics show that first-time moms have a higher PPD than non-first-time moms. This results from multiple factors surrounding the pregnancy and after a birth period. The periods increase the chances of women getting PPD. The t-Test results reject the null hypothesis that first-time moms are not likely to get PPD. The alternative hypothesis is accepted, which states that first-time moms are more likely to get PPD. Despite various factors being associated with the high PPD among first-time moms, the leading cause of PPD is not yet known. This research shows that multiple factors mediate PPD among first-time moms. These factors include job opportunities that one has, the age of the mother, and the level of breastfeeding. Despite the history of depression being a significant factor, anxiety and antenatal depression play an important role in the PPD. First-time mothers are exposed to various fears that increase the risk of getting PPD. This study shows that employment is a significant mediator among women. It is portrayed by the high score of PPD among women seeking survival opportunities. This group of women has experienced significant levels of pressure that affect their mental development leading to anxiety and depression. Most first-time moms are usually unplanned, making them develop employment fears, resulting in anxiety.

Most job-seeking and part-time moms have problems with job stability. During this period, they usually require a stable work environment that makes them relax, knowing that they have something in case their babies need anything. However, this is not always the case among most first moms; hence the development of fear extends to high levels of PPD. Holopainen and Hakulinen (2019) support this assertion by showing that financial pressure is a significant problem among first-time moms. This promotes the development of the postnatal mood disorder, which later severely affects their lives negatively. Low resilience has a critical role in affecting their mental performance (Holopainen & Hakulinen, 2019). This feeling leads to significant harm in both the parent and the child as the parents feel that they cannot handle the current situation that requires maximum economic input. First-time mothers tend to have a sense of loss, making it challenging to cope with the situation, resulting in depression. However, the findings from this research refute the mediation effect of employment among first-time moms. This is because employed participants reported a high level of depression compared to unemployed. This affects the understanding of the role employment plays among first-time women in propagating PPD.

The transition that first-time moms experience also forms a significant problem that leads to PPD. First-time mothers usually experience a problem understanding and living the new motherhood life. It is very challenging as they are used to a life that does not involve a significant input of time, attention, money, and care (Leahy-Warren et al., 2011). They become worried about the life they have to live because of the changes. This issue takes time to manifest, leading to adverse effects. Transition requires social support to enable them to understand what is required of them and prevent enormous pressure that affects their mental well-being. The pregnancy and the postpartum period among first-time moms are vulnerable compared to non-first mothers (Smorti et al., 2019). The period involves a series of events such as social change and psychological and biological effects that make most first-mom vulnerable to various issues such as symptomatology and emotional breakdown. First-time moms are inexperienced during this period, altering their emotional response to the ongoing activities. Women who have children have gone through such a period, and most have sought interventions that enable them to cope.

The age bracket has proven to be a significant mediator in this research, especially among first-time moms. This is portrayed by the finding that women 18 years and below reported the highest level of depression, followed by 19-25. Most of the women in this age bracket are first-time moms and therefore face the problem of being inexperienced. This makes them develop high levels of depression because they are unaware of how to tackle their challenges. Age is a significant mediator variable that has a significant relation with first-time moms. These findings are supported by Silverman et al. (2017) research that shows that experience comes with age, making young and first-time moms have problems handling emotional breakdowns that they experience during the postpartum period.

The descriptive statistics show that women who do not breastfeed their babies have higher PPD than the rest of the group. Those who breastfeed for more than six months reported a low score of PPD. The ANOVA results show that the breastfeeding group means vary significantly, implying that women who do not breastfeed and those who breastfeed have significantly varying levels of depression. The finding suggests that it is crucial for women to breastfeed as it positively lowers their depression levels. The findings reject the null hypothesis that women who breastfeed for a short period have reduced PPD. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis that women who breastfeed for an extended period have reduced PPD is accepted. The positive effect of breastfeeding is backed up by various research study that shows that it has numerous benefits to both the mother and the child.

Breastfeeding has various psychological and nutritional benefits for the mother. Rivi et al. (2020) and Wilson (2018) show the benefit of breastfeeding that helps prevent the development of PPD. The benefits support the finding of this research in explaining the effect of breastfeeding in lowering PPD. During breastfeeding, oxytocin hormones are released, and apart from forming the bond between the mother and the child, it helps lower the development of psychiatric disorders. Additionally, breastfeeding plays a critical role in regulating the patterns such as sleeping and wake-up hence reducing the development of negative emotions. Rivi et al. (2020) finding supports the findings of this research as their results show that women who practice breastfeeding have low negative feelings and have developed positive moods. Hamdan and Tamim (2012) reinforce the findings by portraying that breastfeeding is necessary for reducing PPD. Therefore, women need to consider the benefits of breastfeeding in reducing PPD.

References

Abdollahi, F., & Zarghami, M. (2018). Effect of postpartum depression on women’s mental and physical health four years after childbirth. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 24(10), 1002-1009. Web.

Alomar, M. (2015). Factors affecting postpartum depression among women of the UAE and Oman. Nternational Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 7(7), 231-233. Web.

Borra, C., Iacovou, M., & Sevilla, A. (2014). New Evidence on Breastfeeding and Postpartum Depression: The Importance of Understanding Women’s Intentions. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(4), 897-907. Web.

Figueiredo, B., Canário, C., & Field, T. (2014). Breastfeeding is negatively affected by prenatal depression and reduces postpartum depression. Psychological Medicine, 44(5), 927-936. Web.

Hamdan, A., & Tamim, H. (2012). The Relationship between Postpartum Depression and Breastfeeding. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 43(3), 243-259. Web.

Holopainen, A., & Hakulinen, T. (2019). New parents’ experiences of postpartum depression. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 17(9), 1731-1769. Web.

Klar, S., & Leeper, T. (2019). Identities and intersectionality: A case for purposive sampling in survey‐experimental research. Experimental Methods in Survey Research, 419-433. Web.

Leahy-Warren, P., McCarthy, G., & Corcoran, P. (2011). Postnatal depression in first-time mothers: Prevalence and relationships between functional and structural social support at 6 and 12 weeks postpartum. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 25(3), 174-184. Web.

McIntyre, L., Griffen, A., & BrintzenhofeSzoc, K. (2018). Breast is best… Except when it’s not. Journal of Human Lactation, 34(3), 575-580. Web.

Pope, C., & Mazmanian, D. (2016). Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: An overview and methodological recommendations for future research. Depression Research and Treatment, 2016, 1-9. Web.

Rivi, V., Petrilli, G., & Blom, J. (2020). Mind the mother when considering breastfeeding. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 1, 1-12. Web.

Silverman, M., Reichenberg, A., Savitz, D., Cnattingius, S., Lichtenstein, P., & Hultman, C. et al. (2017). The risk factors for postpartum depression: A population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 34(2), 178-187. Web.

Smorti, M., Ponti, L., & Pancetti, F. (2019). A comprehensive analysis of post-partum depression risk factors: The role of socio-demographic, individual, relational, and delivery characteristics. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 1-10. Web.

Sykes, B., Verma, A., & Hancock, B. (2017). Aligning sampling and case selection in quantitative-qualitative research designs: Establishing generalizability limits in mixed-method studies. Ethnography, 19(2), 227-253. Web.

Wilson, C. (2018). Breastfeeding as a mechanism to reduce postpartum depression with weight as a major contributing factor in Hispanic women. Auctus: The Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity, 1-26. Web.

Appendix A

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 1 (EPDS)

Name: ______________________________ Address: ___________________________

Your Date of Birth: ____________________ ___________________________

Baby’s Date of Birth: ___________________ Phone: _________________________

As you are pregnant or have recently had a baby, we would like to know how you are feeling. Please check the answer that comes closest to how you have felt IN THE PAST 7 DAYS, not just how you feel today.

Here is an example, already completed.

I have felt happy:

- Yes, all the time

- Yes, most of the time. This would mean: “I have felt happy most of the time” during the past week.

- No, not very often. Please complete the other questions in the same way.

- No, not at all

In the past seven days:

Administered/Reviewed by ________________________________ Date ______________________________

Users may reproduce the scale without further permission providing they respect copyright by quoting the names of the authors, the title and the source of the paper in all reproduced copies.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale1 (EPDS)

Postpartum depression is the most common complication of childbearing. 2 The 10-question Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is a valuable and efficient way of identifying patients at risk for “perinatal” depression. The EPDS is easy to administer and has proven to be an effective screening tool.

Mothers who score above 13 are likely to be suffering from a depressive illness of varying severity. The EPDS score should not override clinical judgment. A careful clinical assessment should be carried out to confirm the diagnosis. The scale indicates how the mother has felt during the previous week. In doubtful cases it may be useful to repeat the tool after 2 weeks. The scale will not detect mothers with anxiety neuroses, phobias or personality disorders.

Women with postpartum depression need not feel alone. They may find useful information on the web sites of the National Women’s Health Information Center and from groups such as Postpartum Support International and Depression after Delivery.

SCORING

- QUESTIONS 1, 2, & 4 (without an *)

- Are scored 0, 1, 2, or 3, with the top box scored as 0 and the bottom box scored as 3.

- QUESTIONS 3, 5, 10 (marked with an *)

- Are reverse scored, with the top box scored as a three and the bottom box scored as 0.

- Maximum score: 30

- Possible Depression: 10 or greater

- Always look at item 10 (suicidal thoughts)

Instructions for using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale:

- The mother is asked to check the response that comes closest to how she has been feeling in the previous 7 days.

- All the items must be completed.

- Care should be taken to avoid the possibility of the mother discussing her answers with others. (Answers come from the mother or pregnant woman.)

- The mother should complete the scale herself, unless she has limited English or has difficulty with reading.

Footnotes

- 1 – Source: Cox, J.L., Holden, J.M., and Sagovsky, R. 1987. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry 150:782-786.

- 2 – Source: K. L. Wisner, B. L. Parry, C. M. Piontek, Postpartum Depression N Engl J Med vol. 347, No 3, July 18, 2002, 194-199