Introduction

Solving environmental problems is a worldwide concern. The threat posed by climate change and global warming is pushing mother Earth to the limit. Industrialisation, consumerism in America and globalization, among other drivers of change, have pushed and motivated scientists to find ways to address environmental problems which have continued to plague humanity. Constructions of buildings have become a race for supremacy among big international organizations. Countries consider construction as an economic boost or driver of change, and without it the economy seems to be stagnant and not growing.

Inventions, discoveries and innovations, particularly with regards technology, are introduced any time. While they mostly benefited us in various aspects, they also created disadvantages and problems along the way. Technology can solve some of our problems and help cure sicknesses, but it also creates a problem by itself.

The subject of ecological modernisation is a complex subject about theories, problems, technologies, discoveries and inventions. While it is true that ecological modernisation is about solving environmental problems, there are some aspects that are not so clear. This paper will attempt to talk about some of these aspects, or maybe just a tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

Ecological modernisation is not something new; it spans decades in its implementation. Many works and commentaries have been placed in the open to shed light about ideas and concepts of ecological modernisation. Most notable were the works of social scientists of western European countries.

Implementations of environmental programmes by organisations and businesses have also been parts of organisational management; sometimes it is called strategic management. We would like to argue that environmental programmes and purported solutions came ahead of ecological modernisation.

It can also be said that ecological modernisation is an environmental solution; it aims for a fresh atmosphere, a balanced ecology, a world less threatened by global warming and climate change, a world we all dreamed of.

Environmental problems of the world today are worsened by development, and probably technology has something to do with it. That is a premise which ecological modernisation contradicts. In the literature, we can deduce that ecological modernisation uses technology and the present economic development and advancement as tools to solve the present environmental problems.

There are contradictions in this area which this paper would try to analyze by way of presenting the different sides of ecological modernisation and the various environmental programmes of businesses, organisations and nation states. There are many concepts and ideas on ecological modernisation; our aim is to present how this is done and how it aims for sustainable development.

The Problem and its Background

At first instance, it is not a problem. Ecological modernisation combines economic growth with environmental protection. It is an interesting subject worthy of scrutiny. Authors and scholars have long been studying this to connect to the present studies in environmental preservation.

The problem in this study is whether ecological modernisation is an appropriate approach to solving environmental problems. It is a question that needs analysis of the subject ecological modernisation and the many aspects of environmental solutions being practiced and implemented by individuals, organisations and governments. While it is an interesting and complex subject, or phenomenon, it is also controversial in the sense that there are varying opinions.

It is worth mentioning at this time the background of ecological modernisation before we delve on the pressing issues of whether environmental modernisation (EM) can provide solutions to environmental problems threatening the world’s sustainability.

Ecological modernisation was started in the 1980s by European countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (UK).

Work contributions came from notable social scientists such as Martin Jänicke, Klauz Zimmermann, Arthur P.J. Mol and Joseph Murphy, to name a few. Recent contributions came from authors who hail from countries like Finland, Denmark and Hungary. Considered the founder of ecological modernisation is the German sociologist Joseph Huber.

In the UK, the New Labour launched a sustainable development strategy called ‘Securing the Future: Delivering the United Kingdom Sustainable Development Strategy’. This was a follow-up of the development strategy known as ‘A Better Quality of Life’. The document examined the role of ecological modernisation in the context of the various government agencies and instrumentalities and how this could lead to a sustainable economy.

The strategy did not touch on the real issue of reducing consumption but on how to reduce environmental impact. The government strategy proposed implementation on the following processes:

- Focusing on environmental impacts from waste generated by households and how it could be controlled;

- Improving the information and dissemination with respect to environmental preservation;

- Considering generating funds for environmental purposes;

- Initiating a large-scale forum to acquire public opinion concerning consumption and other related matters;

- Acquiring a concerted effort and outlook on sustainable consumption.

Environmental policy has undergone a lot of changes over the past decade. Ecological modernisation and sustainable development are two of the more popular paradigms that have been used to explain the changes. Although the two phenomena are often conflated, they have distinct features in influencing environmental policy.

Globalisation, Technology and Environmental Reality

In the UK and elsewhere, wastes and waste management are a problem. Construction and demolition waste (C&DW), wastes from food and consumer products, industrial waste, household waste – all these continue to be a problem for individual citizens, including organisations and the various public and private sectors. As people want to preserve their lifestyle, protecting the environment and public health remains to be a focus of concern.

Thousands of years ago, people learned to dispose of their waste outside their settlements. People lived simple lives and so wastes were quite simple, merely composed of food scraps, mussel shells, bones, etc. The people built dump sites to provide hygiene to their dwelling.

Presently in the UK, an estimated 330 million tonnes of waste annually have to be disposed to incinerators and landfills. Disposing of these tonnes of wastes alone can create tonnes of problems. Incinerators and landfills also create environmental impact. Organisations and governments have implemented programs of environmental management, such as reduction of production, or implementing the 3Rs (recycle-reuse-reduce). But did it address the mounting environmental problems?

Now, with technological innovation, waste materials can be transformed into electricity. This will provide jobs to engineers, geochemists, scientists, planners, and many other professions. Environmental laws have to be altered to give way to an immediate and fast waste disposal.

Wastes come from households and businesses, and also from construction and demolition, sewage, farm waste, from mines, etc. Electronic and clinical waste recorded a substantial increase, but C&DW has contributed about 33 percent of the total waste.

Technological innovation – it has been said – added with environmental policies and programs, is the thrust of ecological modernisation.

Globalisation, on the other hand, has produced wonders for organisations and businesses. But it has multiplied problems in this age of technological innovations.

Globalisation has revolutionised products, markets, economies, events, activities, organisations and more. Standardization and adaptation are aspects of globalisation, and this involves products, multiple of products that have to be discarded after usage. Due to globalization, national borders are not very important now. There is interconnectedness of organisations and businesses, while countries focus more on deregulation, privatization and liberalization of industries, and the importance of world markets.

Globalisation has transformed the world and the inhabitants who formed organisations. In 1995, developed industrialized countries which composed the Organization for Economic and Development (OECD), started to formulate the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), an agreement which is similar to the World Trade Organization agreement concept. This move was the OECD’s response to globalization in investments.

The terms of the agreement were, of course, in favor of the OECD member states and the developing countries who were non-members had no choice. The treaty had a neo-liberal characteristic which environmentalist organizations attacked. It was also in favor of multinational corporations and put nation-states at the disadvantage. The fact is that there has always been a movement to globalize investments and that this would jeopardize the developing countries and put more economic power to developed industrialized countries. The MAI was perceived as too neo-liberal.

The question is what about the environmental policies. For sure, they would be introduced and the developing countries could do nothing but follow the dictates of this grouping. It is already felt the world over that the OECD and the EU are strong political groupings that can influence world policies. With continued deregulations in these countries, multinational corporations have much more say in political policies, particularly the ones which pertain to environmental regulations.

Developed industrialized countries can influence and dictate developing countries. Multinational firms can do the same. They have the whole world as its market field that they can offer a wide array of products and services. Firms expand and grow. One aspect of globalisation is that firms can assign departmental functions, such as marketing, finance, operations, human resource management, and accounting to other firms. This is known as outsourcing.

Most firms are globalised. In this new setting, some traditional processes may remain but governance and structural arrangements are different. Some differences include the structural set up in which the top managers and their boards now assume functions different from traditional firms. The structures and functions with respect to the roles of top managers and board of directors, the CEO or the Managing Director, and the composition of the Board of Directors are not the same as in the traditional firms.

Green supply chain management is another innovation in the age of globalisation. There have been drivers of change for the introduction and implementation of green supply chain management. One of these is the continuing demand and attention paid to health issues by consumers.

The food industry has been continuously adding innovations due to consumers’ demand for healthy food (diet food) and to ‘green’ their supply chain. Other organisations adopt their own environmental programs to minimize environmental impact. But there has been no such program for consumption reduction, which is one of the issues raised against ecological modernisation.

Supply chain is a primary source of products. Core materials cannot become real products without proper implementation of supply chain management. But supply chain must be handled in a systematic way. Supply chain has evolved too, from mere extraction to application of different methods in order to provide quality products.

The term quality has many meanings in the new context of supply chain. While before quality applies to durability and long-lasting, now quality applies to the entire process of extracting the material to become a product. Quality should be ‘green’ and must not threaten the environment. Quality means good business.

Technology has revolutionized various aspects of production and the information systems. Information systems have a lot of risks. Security measures and necessary risk management processes should be implemented to avoid uncontrollable scenario in case of a virus attack.

The concepts and outcomes of globalisation described above are a portion of the realities that ecological modernisation has to deal with. Historically, globalisation did not attract so much attention among academics, as noted by Mol, rather it was the environmentalists and scholars in the 1970s who took notice of the relationship of globalisation processes and the environment and globalisation’s negative effects. Mol and Spaargaren’s ideas are influenced by the results of globalisation, the negative effects on the environment and its influence on environmental politics.

Ecological Modernisation: Definitions and Concepts

Views and opinions about the environment, the effects of globalisation and the apocalyptic literature were prevalent in the 1970s and the early 1980s. When ecological modernisation became a hot topic, technology was one of the recommendations. Climate change would soon be addressed with technological innovations. In other words, the proposals were provided with technical recommendations. With technologies and sources of energy becoming the main interests, talk of globalisation effects slowly disappeared in thin air. Optimism and new outlook emerged, linking ecology and the economy.

Economic activities and by-products could be made to provide environmental benefits. Cost benefit analysis would be made to determine what was not good for pollution control so that certain values would be allocated accordingly.

Maxeiner and Miersch (1996) wrote a book titled Öko-Optimismus which provided an optimistic outlook for growth and sustainability in the coming century. From then on, numerous studies were conducted which focused on environmental programs of institutions and governmental agencies. The effects and devastations brought about by globalization and industries were put into the sideline. Such studies and subjects had themes about dematerialization, ecology, environmental management, and technological innovations that could be used for environmental preservation.

Ecological modernisation, as an environmental science, has become a full-fledged subdiscipline. This is because in a span of a few decades, it is filled with well-established set of literature and ideas and supported by a general social theory. Since it is a growing theory and is becoming popular, it is the object of several criticisms from different fronts.

The theory of ecological modernisation spawned theoretical discussion about the environment and sociology and contributed to making this area of study more attractive to subjects on environment, development and policy-making.

Other concepts and terms linked to ecological modernisation include “eco-efficient innovation”, or the use of technology to provide environmentally-friendly means of production. Ecological modernisation theory offers ecological stability and balance in the midst of economic success; it is promoting a green environment in a democratic atmosphere.

Ecological modernisation focuses on the production aspect of industries and its effect on the environment. The focus turns to resource efficiency and effective supply chain. Moreover, the exact theoretical and conceptual meaning of ecological modernisation cannot be determined, but it is more focused on theories of modernity.

Other concepts linked ecological modernisation on technological innovation as a way of solving environmental problems in the post industrialization age. What is remarkable and interesting on the ‘new belief’ and new system is that instead of stopping and controlling industrial development, ecological modernisation theory suggests that it is the ‘best option for escaping from the ecological crises of the developed world’.

Hajer (1995, p. 25) stresses that ecological modernisation recognizes the structural character of the environmental problem but existing political, economic, and social institutions can be used to solve environmental problems.

Ecological modernisation (EM) is a theoretical approach to understanding how industrialised countries deal with environmental problems. The idea was to combine technological innovation and new management technique and structures in addressing environmental problems.

Two features of ecological modernisation let us understand that it is an optimistic approach: first, environmental improvements are ‘economically feasible’; second, ecological modernisation states that political actors are building new and different relationships to enable environmental protection ‘politically feasible’. There is a link between ecological modernisation and political modernisation. The results of ecological changes depend on ‘changes in the institutional structure of society’.

Spaargaren argued that the main point of ecological modernisation is the need for political intervention in its implementation. It cannot be effective if the political structure is taken into the sideline. The political policies have to be incorporated into the processes.

With ecological modernisation, environmental problems can best be solved through further advancement of technology and industrialisation.

Critics say that ecological modernisation, or ‘sustainable capitalism’, is not possible. This criticism is influenced by the concepts of neo-Marxist perspectives.

In the Netherlands for example, the country has experienced interactive approaches to environmental policies, and it is from this country that ecological modernisation originated. Their environmental policy has been carried on from the early 1980s.

An important aspect of ecological modernisation is that the role of the nation state is more pronounced. Inside the organisation, it is not anymore where the top management directs the reins of power; there is delegation of powers.

As a political program, ecological modernisation was used to interpret environmental policies in the countries Germany and the Netherlands. Weale said that EM was used to attack the pollution control policies in Germany of the 1970s. The pollution strategies provided mechanisms such as using a specialist branch of the government; that the environmental programs were well understood; that the technologies at that time were adequate; and that there should be a balance between environmental protection and sustainable development.

These strategies proved to be ineffective in solving environmental problems at that time since they resulted in problems ‘postponed’ instead of being solved. However, it resulted into a ‘reconceptualization’ of the existing policies and that environmental protection was seen as a source for future growth.

Authors, scholars and policy makers and those who controlled the political spectrum started to make noise on what became an interesting subject of discussion, ecological modernisation

Hajer provided an interpretation on ecological modernisation which was different in that it was a reaction to the environmental movements going on in the 1970s. Hajer indicated that environmental problems could be solved using the existing policies and institutional framework of society. In Germany, Hajer upheld the pollution policies of the 1970s.

Hajer questioned whether ecological modernisation should come ahead of ecological crisis in matters of discussion over environmental policies. He pointed out that ecological crisis should be the main agenda and starting point before the topic of ecological modernisation is discussed. Hajer’s argument is that adding an element of ecology to the world’s modernisation process does not solve environmental problems.

The Theory

A hypothesis of ecological modernisation theory is that the design and processes of production, including evaluation and it performed in the value chain, are based on ecological criteria.

Advocates of ecological modernisation criticized other sectors of environmental social science for merely looking at the capitalist system of production, thus ignoring the more concrete and ecologically driven activities in production. Mol has proposed the three spheres in the network in which stakeholders engage in interactions for ecological modernisation activities:

- Policy networks which concerns with manufacturer-government agency relationship that uses administrative structures;

- Economic factors in a network focusing on economic interactions that follow economic rules;

- Social networks working on the level of social interaction between economic sector and civil society groups.

Within the networks, transformations occur that point to environmentally focused programs.

Ecological modernisation advocates and theorists posit that a new era for industrial society happened during the time ecological modernisation took its roots. During this time, technologies, entrepreneurs and capitalists brought in new perspectives for industries. It was a period of the so-called ‘reconstruction’ wherein a new ecological sphere emerged independent from the three mentioned spheres. This sphere is marked by independence and is empowered by political and economic structures of society.

The explanation here focuses on the emancipation aspect, such that it is independent from the other three spheres, and true to its name ecological modernisation. Ecological modernisation therefore is about a political program, that also refers to industrial change and making the ecology balanced through the political and economic structures.

Sustainable Development

It is the ecological concern that has shifted and not the concept of ecological modernisation. This is Dryzek’s opinion. The term sustainable development was first used in the 1980 World Conservation Strategy but the World Council of Churches also made use of the term in 1970.

The World Council of Churches stressed that the world’s future revolved around justice and ecology. Justice should refers to ‘correcting maldistribution’ of products of the planet and focusing on helping poor countries in order to equalize the distribution of the earth’s resources.

Ecology refers to humanity’s exploitation of the Earth’s resources. Society must be united in using the Earth’s resources sufficiently so that all can use it indefinitely in a sustained manner. Society must not be unjust and abusive of the environment. ‘A sustainable society which is unjust can hardly be worth sustaining. A just society that is unsustainable is self-defeating.’

Environmental sustainability pertains to the future generation and thus can be referred to as a legacy. Sustainability can be one of the most hard-earned propositions and activities humanity can have when speaking of the future since every living thing creates environmental impact. Even a small dog or cat can have environmental impact.

Production and constructions of buildings and all man-made structures have environmental effects. There are construction operators and owners who employ environmental safeguards such as building sewage treatment plants, water-treatment systems, and other waste-management systems. Organisations recognize that eliminating waste requires a lot of resources and political will to implement. Wastes and hazardous materials continue to exist for as long as constructions and productions continue.

The issue here is not on implementing environmental safeguards alone but how this should be incorporated on the process. This is where ecological modernisation concept comes in. Ecological modernisation is not concerned on one aspect of production but on the entire process. Sustainable development by way of environmental sustainability can provide the solution.

It can be questioned how sustainable development can influence regulation. Sustainable development needs ‘incremental levels of change’. Sustainable development can be attained by focusing on the ecological wellbeing. What can be said as burdensome is that it would require economic and administrative changes in the structures which created the problem in the first place.

Hajer pointed out that despite the challenges, sustainable development provided states with new consensus. There was no broad agreement on the part of the states that environmental programs would be a part of the sustainable development framework.

Comparing Ecological Modernisation with Sustainable Development

The World Commission on Environment and Development44, which created the paper Our Common Future, combined several issues into one; these are the issues on ‘development, global environmental issues, population, peace and security, and social justice’.

Sustainable development considered several issues that ecological modernisation had no particular programs. In line with this, Jacobs adds that sustainable development did not refer to economic aspects but on purely ‘ethico-political objectives’.

Studies have shown that ecological modernisation is an ‘expression’ of sustainable development, or that ecological management is necessary to have a sustainable development. However, the two should not be conflated because it would mean that it is already happening or being done. It would also be counterproductive with respect to the environmental policies that are being done to attain sustainable development.

Political Implications

Environmental innovations have three distinct features with respect to political implications. First, environmental programs need to have political support, and this all the more means that ecological modernisation is a political exercise; second, environmental innovations address environmental problems that are global in scope and therefore they have global market potential; and third, the global economy needs environmental innovations since natural resources are becoming scarce and depleted.

The most important implication of ecological innovations lies in the fact that politicians cooperate with industries or firms which also seek political and regulatory support for their technologies. An example of this is the company Philips which supports the EU policy on ‘energy-saving’ products because the company has been marketing power-saving light bulbs.

Also, the government can encourage ecological modernisation by way of its political power and influence. It can enforce regulation through taxes, for example, the government can switch from income and employment taxes to taxes for resources and wastes. Businesses will then react and forced to institute efficient waste disposal and effective production.

Ecologically-modernized states

Examples of countries which are said to be ecologically-modernized are Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. Japan has made it to the top because of energy measures it has instituted to its economy. There have also been empirical studies conducted on Japan which found structural changes in the economy along with improvements in environmental programs.

Japan has been hailed by observers as an ‘ecological front-runner’ due to programs separating consumption from economic development. It is the first non-western country to implement successfully the concept and features of ecological modernisation, but there has been little studies afforded on Japan’s situation. Its implementation on air pollution solutions in the 1970s has been considered an ecological modernisation paradigm. There are some empirical studies that proved that Japan’s economy acquired structural changes and there were also recorded changes in environmental programs which led to environmental improvements.

There have been criticisms on Japan’s implementation and successes on ecological modernisation. One of these states that Japan did almost like committing ‘political hara-kiri’ since environmental improvements only occurred because Japan was able to transfer manufacturing in other countries. Also, environmental improvements camouflaged some environmental degradation like loss of tropical rainforests and abuse of endangered species.

Japan has an addiction of some sort to construction since it spends about 8 percent of its GDP on construction. Japan did not have an environmental law until 1997 so that there was much destruction of the natural habitat and also threatening the various species in the forests. Other serious environmental abuse included water pollution, coastal abuse, destruction of natural habitat and biodiversity.

Ecological Modernisation in Southeast Asia

There have been studies on the concept and implementation of ecological modernisation in Southeast Asia, particularly the pulp and paper sector. Local manufacturing firms adopted cleaner technology in constructing facilities.

David Sonnenfeld argued that the construction was not totally ‘ecologically-modern’ considering that pulp production in those areas resulted in exploitation of forests but added with fast-growing exotic trees. Technology firms should be encouraged to introduce ecologically modern approaches so that small businesses can thrive and also provide jobs for the local inhabitants.

In a study, Vietnam and other emerging tiger economies were found to lack ‘environmental regulatory apparatus’ and government policies and programmes for instituting technological change for a sound environmental atmosphere. This was the result of a study by Jos Frijns and several authors who also said that the country lacks a coherent national environmental movement to pave the way for ecological reforms. Ecological modernisation theory is not yet taking a powerful root in Vietnam to provide environmental reform processes. But Vietnam could advance the present programs into a stronger environmental policy.

The Precautionary Principle

The precautionary principle is used in determining risks to the environment. The principle states that there is a threat of an environmental degradation but whether it will actually occur is not certain. This situation is similar to other risk identification processes. The risk society that we are in the midst is an outcome of the industrial revolution and the various technologies introduced day in and day out. There is an unprecedented scientific progress which is the root cause of ‘contemporary environmental risks’.

The industrial revolution was a period characterized by major events which introduced a lot of changes in the workplace and organisations. Modern capitalism emerged after a transition period over several centuries, during which the conditions needed for a capitalistic market society were created.

Risks account not only in physical terms, but also in abstract terms like financial and economic outcomes. Environmental problems, accidents and deteriorating health of workers were some of the risks. Workers who were not provided adequate basic necessities performed poorly and injured themselves.

Risks and threats are multiplied day in and day out because of the endless interconnection of computers via the Internet. While before computer connections were confined to a few other computers by way of cables, now it is endless. And as risks and threats are multiplied, ways of countering it through anti-viruses have got to be endless too. This means programmers and IT security experts have to apply continuous protection and constant maintenance to the IT infrastructure.

Ecological Modernisation and Sustainable Development

Ecological modernisation has been praised by some authors. O’Neill suggested that ecological modernisation is an innovative way of determining national environmental policy while being a part of the changing international context. Ecological modernisation considers environmental protection as allied with sustainable growth.

Ecological modernisation and sustainable development can go together but cannot be conflated. Another opinion draws a combination of environmental and industrial concerns to that will lead to sustainable development.

The World Commission on Environment and Development developed the concept of sustainable development in the Our Common Future which, according to Langhelle, had several similarities with ecological modernisation. Some commentators argued that sustainable development, as expressed in Our Common Future, is the result or an expression of ecological modernisation.

Weale voiced out almost the same opinion, while Hajer (1995, p. 26) also said that the Our Common Future is a document that explains ecological modernisation.61 These authors agree on one point: that ecological modernisation and sustainable development are one and the same. But there are others, such as Dryzek (1997), Jänicke (1997) and Blowers (1998), who argue that these two are overlapping and that it cannot be ascertained as to which of the two has stronger policy implications.

Ecological modernisation and sustainable developments have always been the subject of debate by authors and scholars. Ecological modernisation is applied and used in different ways by different scholars. Some use EM to mean technology advancement while others use it to mean different policies in environmental programs. But there also others that use it to mean a new system or a new belief.

Mol & Spaargaren uses EM to explain social theories about the modern world with a new set of political policies and programs. On the other hand, Christoff explains the phenomenon by introducing two versions: a ‘weak’ and a ‘strong’ ecological modernisation version.

Practices of Ecological Modernisation

Concepts of adding value to supply chains which include green supply chain management and corporate social responsibility in business organisations can be considered ecological modernisation aspects or practices. Adding value to supply chain became popular in the 1980s, the time ecological modernisation was founded by the German sociologist Joseph Huber along with other European social scientists.

Green supply chain management motivates supply chain actors to produce valuable products with less material coming from the environment. Supply chain management, which is about the process of extracting raw materials to produce a product, includes organisations and people who make the product. The objective of supply chain management is to reduce environmental abuse and to provide results of a balanced ecology.

Also, green supply chain management promotes green logistics and related measures that include safety of workers in the workplace, workers’ benefits, green engineering, and other environmental issues. Another optimistic result of green SCM is the enhancement of a closer relationship between members of the supply chain by way of coordinated efforts and effective communication. All partners work for value added chain and environmental preservation.

Technology to generate power in homes is an example of ecological modernisation. In the UK, this is becoming popular and a thrust by the government. Domestic micro-generation provides electricity to household owners. If this is fully implemented, it will reduce 15% of CO2 emissions by year 2050.

The UK government identified sustainable technologies along with the social and economic results from its implementation. The program was known as the Sustainable Technologies Programme (STP) which had some negative implications, such as the high cost of micro-generation. High cost however, was due to a combination of heat and power, solar photovoltaic, and wind energy.

Micro generation makes use of technologies in the generation of heat and power. The maximum thermal output can range below 45kWt or an electrical output of 50kWt. Heat and power are generated using the wind, solar photovoltaic (PV), and also hydro power. Heat generation also comes from biomass, solar thermal and heat-pumps. Micro CHP produces heat and power from renewable or fossil fuels. Increased use of renewable energy, including micro-renewable, can make an important contribution in the efforts to reduce carbon emissions in support of climate change and renewable energy objectives.

The government is strongly taking the role of ensuring environmental safety and sustainability in order to reduce climate change. (Caird & Roy, 2010)

One example is the implementation by the Scottish Government to provide 50 percent of electricity to its population using renewable energy by year 2020. This year, it has set just about 31 percent. Micro-renewable energy will meet these targets to make a historic environmental event for the country. Other renewable energy sources come from wind and solar energy that will surely make an impact by reducing climate change. (Watson, 2004)

There is also the Green Business Plan Guide of organisations which provides similarities of industrial ecology and green SCM, for example: supply chain which is about enhancement of environmental development; supply chain partners to take an active role in producing environmentally friendly products; Information Technology to be utilized in the production of environmentally-friendly products; traditional methods in supply chain to be refined or reprogrammed to correspond with new methods and new concepts; green supply chain management to promote/preserve the ecology.

Implementing the Environmental Management System in organisations is an ecological modernisation feature. In the UK, this is carried out by adopting the ISO Standard 14001. It is incorporated in the policies of organisations also taking into account the legal requirements. This move also considers the political aspect of environmental modernisation.

Policies are for environmental improvement. ISO seeks to improve environmental programs. Organisations should continue to provide innovations and changes in the EMS implementations.

Discussion

During the early years of its conception, EM faced various criticisms because it was perceived as having technocratic tendency and civil society and political institutions were being ignored. Then in the 1990s, EM underwent several innovations by way of altering the cultural, political and economic factors so that environmental changes could be integrated with production and consumption.

Ecological modernisation states that the ordinary citizen has a role in environment preservation but is not sure in addressing the environmental protest that should be brought to light and discussed. The protester in the environmental activism only becomes a challenger.

By promoting ecological modernisation as technological fix for environmental problems, it acts like a ‘Trojan horse’ for individuals and industries which are not keen to promoting environmental protection. Other governments have adopted a neo-liberal way which addresses some environmental issues, but the activity is only a part of their major political agenda. An example is the European Green parties which had difficulty when they joined the government.

Another criticism of ecological modernisation is the Marxist view that the capitalist order does not permit environmental reform other than the so-called ‘window dressing’ being done by capitalists or industrialists. Scholars argue over ecological modernisation’s reformism which only promotes ‘light green’ instead of the radical change that society should adapt to its environmental programs and actions.

Despite the successes of ecological modernisation in its implementation in the developed industrialized nations, particularly on the application of command control regulation, there has been criticism that it does not fit to the challenges that modern forms of systems and economies create.

Some criticisms said that ecological modernisation is expensive and requires a lot of activities for governments and organisations. There are also concerns that it cannot change the behaviour of peoples manning the systems and governments.

There are those who question why command and control should be present in the first place. Ecological modernisation and sustainable development should not influence regulatory structures and environmental problems must be voluntary on the part of organisations.

Another argument is that the law evolves as part of people’s need, but ecological modernisation requires the law to pave the way for its successful implementation. The state can provide the way for change but without altering the existing fundamental structure. Thus this criticism is just on the technical aspect and it can be corrected.

Incremental change also corresponds with Weber’s idea of bureaucratic rationality wherein complexity and problems caused by changes can be addressed through bureaucracies and the force and unity of governance. Phenomena like ecological modernisation and sustainable development can be addressed through what the existing system can offer as solutions. Difficult problems can be solved through the capability, technical expertise and professional competence of the people in the system.

Positive Points

The Micro-generation Strategy implemented by the UK government aimed to provide the conditions wherein micro-generation becomes an alternative source of electricity for local households and even businesses. This is an example of technological innovation to support environmental programmes that will reduce greenhouse gases and fuel consumption.

The government agency announced that it was changing the government’s planning system when it came to micro-generation. The changes would make much easier the way homeowners would apply and install their equipment in their homes. Homeowners will now find it easy to install energy related technologies including solar panels, photovoltaic cells, and wind turbines.

The high capital costs of micro energy and micro-renewable technology, lack of understanding of the technology, and lack of knowledge where to find source of funds, are the main barriers to micro energy generation up take and reduction in climate change by domestic users.

The process of ecological change should be accompanied with continuous institutional reforms, using scientific and technological strategies along with economic dynamics.

Ecological modernisation focuses on the production aspect of industries and the environmental impact. Resource efficiency and effective supply chain are some of its programs. The strategy does not touch on the real issue of reducing consumption but on how to reduce environmental impact.

The question posed in this paper can be addressed to a comparison of the present implementations of green supply chain management by organisations in the United States, the UK and other countries around the world.

Green supply chain aims to reduce environmental impact and does not aim for reduction of consumption. The main point in green supply chain management is to reduce waste. One of EM’s features is to continue the industrial development but also provide avenues for environmental preservation. The two should go together.

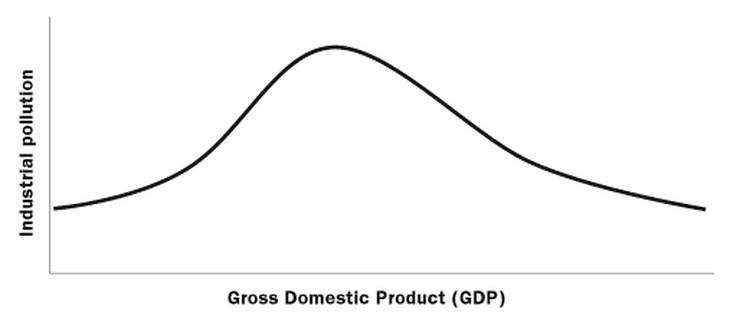

Figure shows the Kuznets curve which demonstrates how GDP rises as industrialization peaks. Ecological modernisation causes GDP to rise because of increased economic activity, but pollution rises along with it, and then it peaks and eventually falls. Causes of pollution include chlorofluorocarbons, sulphur gases, but there are no other gases. There is no fall in carbon dioxide emissions.

The Kuznets curve can provide an outlook of what will happen if a country implements ecological modernisation. There is positive impact on economy and the environment.

Developing countries can follow the example and learn from experience of developed countries. Ecological modernisation is a model example of environmental preservation and protection, but some stages in production and other inefficient aspects of economic growth could be avoided. This can prevent pollution in the long run.

Ecological modernisation promotes preventative environmental management. This involves resource efficiency, reduction of waste and pollution prevention that should be incorporated into production planning and industrial processes. It is a part of the entire industrial processes rather than on some aspects or parts of production alone.

Conclusion/Recommendations

Based from the literature and from the analysis, there are more reasons to believe that ecological modernisation is an appropriate approach to solving environmental problems.

Ecological modernisation did not emerge in as a phenomenon enforced upon nation states but it emerged gradually. The founders of this system and the developed industrialized countries which first observed its importance to the environment found it to be effective in reducing pollution.

The remarkable effect of ecological modernisation is that it does not contradict economic development, rather it states that the status quo, as far as the economy is concerned, should continue and focus on environmental programs.

The need for political support is another important factor in the success of ecological modernisation. This puts into clear understanding why it is important in this age of globalization. All the barriers to put an activity into action are diminished. Political support, organizational support, and society’s cooperation are placed into one whole agenda of pursuing environmental reforms for the good of the entire ecosystem.

Bibliography

Barrett, FD & DR Fisher, Ecological modernization and Japan, Routledge, Oxon and New York, 2005, pp. 8-10.

Barry, J, ‘Towards a model of green political economy: from ecological modernisation to economic security’, in L Leonard & J Barry (eds), Global ecological politics, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, 2010, pp. 116-117.

Bilitewski, B, K Härdtle, A Weissbach, & H Boeddicker, Waste management, Springer, New York, 1994, pp. 1-5.

Breukers, S, Changing institutional landscapes for implementing wind power: a geographical comparison of institutional capacity building, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2006, pp. 35-36.

Caird, S & R Roy, Adoption and use of household micro generation heat technologies, Low Carbon Economy, 2010, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 61–70.

Cole, M, ‘Limits to growth, sustainable development and environmental Kuznets curves: an examination of the environmental impact of economic development’, Sustainable Development 7, 1999, 87-97.

Elling, B, Rationality and the environment: decision-making in environmental politics and assessment, Earthscan, London, 2008, pp. 186-190.

Emmett, S & V Sood, Green supply chains: an action manifesto, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., London, 2010, p. 10.

Fiorino, DJ, The new environmental regulation, Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press, 2006.

Fisher, DR & WR Freudenburg, ‘Ecological modernization and its critics: assessing the past and looking toward the future’, Society & Natural Resources, 14: 8, 2001, pp. 701-709.

Hajer, M, ‘Ecological modernisation as cultural politics’, in S Lash, B Szerszynski & B Wynne (eds), Risk, environment & modernity, Sage Publications, London, 1996.

Hawkins, R & HS Shaw, The practical guide to waste management law, Thomas Telford Ltd., London, 2004, pp. 1-4.

Humphrey, M, Ecological politics and democratic theory: the challenge to the deliberative ideal, Oxon, Routledge, 2007, pp. 82-83.

Jänicke, M, Ecological modernisation: new perspectives, Journal of Cleaner Production, 16 (2008), pp. 557-565.

Langhelle, O, Why ecological modernization and sustainable development should not be conflated, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 2000, 2, pp. 303-322.

Lee, R & E Stokes, Ecological modernisation and the precautionary principle, in J Gunning & S Holm (eds), Ethics, law and society, Volume I, Ashgate Publishing Limited, Hants, England, 2005, p. 103.

Leonard, L & P Kenny, Sustainable justice and the community, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, 2010, pp. 114-115.

Leroy, P & J van Tatenhove, Political modernization theory and environmental politics, in G Spaargaren, APJ Mol, & FH Buttel (eds), Environment and global modernity, Sage Studies in International Sociology, London, 2000, cited in DR Fisher and WR Freudenburg, Ecological modernization and its critics: assessing the past and looking toward the future’, Society & Natural Resources, 2001, 14: 8, pp. 701-703.

Liefferink, D & APJ Mol, Voluntary agreements as a form of deregulation? The Dutch experience, in U Collier (ed), Deregulation in the European Union: environmental perspectives, Routledge, New York, 2000, pp. 181-183.

Mol, APJ, Globalization and environmental reform: the ecological modernization of the global economy, The MIT Press, United States of America, 2001, p. 47.

Mol, APJ, ‘Social theories of environmental reform: towards a third generation’, in M Gross, Environmental sociology: European perspectives and interdisciplinary challenges, Springer, New York, 2009, pp. 26-27.

Mol, APJ & DA Sonnenfeld, Ecological modernisation around the world: perspectives and critical debates, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., 2000, p. 140.

Mol, APJ & DA Sonnenfeld, ‘Ecological modernisation around the world: an introduction’, in APJ Mol & DA Sonnenfeld (eds), Ecological modernisation around the world: perspectives and critical debates, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., London, 2000, pp. 3-12.

Mol, APJ & G Spaargaren, ‘Ecological modernisation theory in debate: a review’, in APJ Mol & DA Sonnenfeld (eds), Ecological modernisation around the world: perspectives and critical debates, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., London, 2000, pp. 17-20.

Newell, P & M Paterson, Climate capitalism: global warming and the transformation of the global economy, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010, p. 24.

O’Neill, K, Global to local, public to private: influences on environmental policy change in industrialized countries, paper presented at the 14th World Congress of Sociology, Montreal, July, 1998, cited in DRFisher & WR Freudenburg, ‘Ecological Modernization and its critics: assessing the past and looking toward the future’, Society & Natural Resources, 2001, 14: 8.

Parker, B, Introduction to globalization and business: relationships and responsibilities, Sage Publications, London, 2005, p. 352.

Pellow, DN, A Schnaiberg & AS Weinberg, Putting the ecological modernisation thesis to the test: the promises and performances of urban recycling, in APJ Mol & DA Sonnenfeld (eds), Ecological modernisation around the world: perspectives and critical debates, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., 2000, p. 109-113.

Roberts, J, Environmental policy, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011, pp. 116-117.

Spaargaren, G & B Van Vliet, Lifestyles, consumption and the environment: the ecological modernisation of domestic consumption, in APJ Mol & DA Sonnenfeld (eds), Ecological modernisation around the world: perspectives and critical debates, Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., London, 2000, pp.50-53.

Watson, J, Co-provision in sustainable energy systems: the case of micro generation, Energy Policy, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 1981-90.

Weale, A, The new politics of pollution, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1992, p. 31.

Wisner, J & S Linda, Process management: creating value along the supply chain, Thomson South-Western, New York, 2008, p. 598.

Wolven, L, Life-styles and energy consumption, Energy, 2001, 16(6): 959.