Introduction

The purpose of this paper is the analysis of the crisis that the subsidiary of East Japan Railway Company Tessei was facing in 2005. As Tessei’s primary function was performing cleaning operations of high-speed trains, customer and employee dissatisfaction indicated low performance. The situation was further complicated by the stigma attached to cleaning workers. Few people wanted to take the job, which caused a high turnover and an increase in part-time employment. Understanding the reasons behind the company’s underperformance is essential in ascertaining the most suitable solutions that would restore Tessei’s image, employee satisfaction, and financial situation.

Analysis

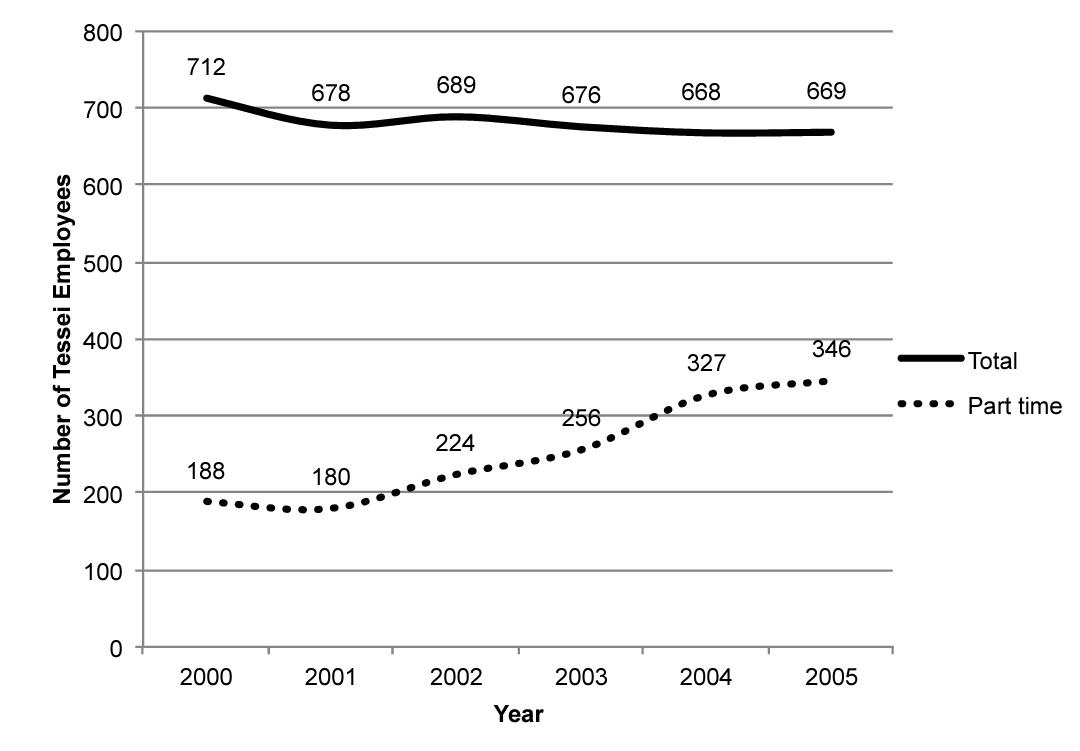

Having taken a closer look at the company background, it becomes apparent that management’s hiring policy became a catalyst for future problems. Appendix A shows that from 2001 until 2005, the number of part-time employees increased almost twofold – from 180 to 346 (Bernstein & Buell, 2015, p. 11). At the same time, the number of full-time employees remained relatively the same, with a minimal decrease from 689 in 2002 to 669 in 2005 (Bernstein & Buell, 2015, p. 11). The original intent was the reduction of expenditures, however, in reality, such a decision incurred more costs as the number of full-time employees did not change drastically.

Another mistake on the management part was the identity of the employees. Most of the workers were 53 years old, with complicated career employment histories (Bernstein & Buell, 2015, p. 2). As a result, the bulk of Tessei was formed by people who are not suitable for enduring the physical demands of the job and have status issues. As evidenced by the comment of a Tessei employee, many of the workers faced discrimination based on job status (Bernstein & Buell, 2015, p. 7). It is no surprise that Tessei had such a high turnover.

Solutions

The first solution is to remove part-time employees from the roaster entirely. First, it will free the resources that the company uses to compensate for part-time workers, who receive almost the exact same wage as full-timers – ¥910 per hour opposed to ¥1050 (Bernstein & Buell, 2015, p. 2). With this money, Tessei could increase full-time wages, thus making the positions appealing and attractive to younger people, who are physically fit to clean the trains regularly. Not only does this solution resolve the problem of fiscal deficit for the company, but it also increases the job satisfaction of its employees.

The second solution is to change the mentality of the workers, specifically their attitude towards the job. However modern bullet trains are, cleaning operations are not new. Deery et al. (2019) argue that “One of the principal techniques of combatting attributions of dirtiness is through reframing the meaning of the work by emphasizing the positive nature of the means or the ends” (p. 637). This implies that all Tessei has to do is rebrand the workers as high-class specialists able to perform a cleaning operation of a high speed train within seven minutes. It will also add more credibility to the decision to increase full-time wages.

Conclusion

Altogether, it should be evident that inadequate hiring policy and cultivation of dirty job stigma were the underlying reasons behind Tessei’s crisis. The company’s attempts to cut expenses by increasing the number of part-time employees were foiled by continuing expenses on full-timers. Weary of the discrimination against cleaning crews, workers did not stay at the job for long. Both these problems can resolved by the removal of part-time employees and using the excess of money for compensating full-time ones while reframing their job in a more positive way.

References

Bernstein, E., & Buell, R. W. (2015). Trouble at Tessei. Harvard Business School Case, 1-16. Web.

Deery, S., Kolar, D., & Walsh, J. (2019). Can dirty work be satisfying? A mixed method study of workers doing dirty jobs. Work, Employment and Society, 33(4), 631-647. Web.

Appendix A