Abstract

Different stress levels can be triggered by daily experiences and can affect human beings in several ways, such as emotional and physical. Smoking might be considered as one of the ways to cope with stress. This research investigates whether the perceived stress levels and smoking habits in middle-aged adults are related to each other. The study is based on a questionnaire answered by people from age 30 to 65 years, who responded to an online survey inquiry available for a certain period, where demographic questions, perceived stress scale (PSS) and smoking habits were investigated. Qualtrics software hosted the data collection and SPSS software was used to analyze it. Overall, there were 103 valid responses received from the research participants. Demographic data suggest that the larger part of responders were females, the average age of participants was 30 to 40 years old, and the majority of the individuals were married and the majority of the participants hold a bachelor’s degree. The cross-tabulation was performed between the variables of participants’ age and their smoking habits. It was identified that the habit of smoking differs with the age of the participant, suggesting that older people tend to smoke rarely. The multinomial regression technique was conducted and three models were evaluated. The first model was associated with determining the effects of stress driving the middle-aged individual to smoke. Stress has a significant impact on smoking and nicotine consumption, according to research findings. The second model considered whether smoking helps participants relax and came to the conclusion that it doesn’t because of its negligible impact. The third model was emphasized in determining whether smoking can reduce the perceived stress level where the model was found significant.

Introduction

Human stress can be briefly described as an automatic body reaction to real sensed challenges that act upon individuals’ mental and physical well-being. These perceived challenges are normal when it is presented in moderate amounts; however, too low or too high manifestations will bring up issues. As an example, chronic stress is directly linked to anxiety, depression, and cardiovascular diseases (Alex, 2019). Stress is a very acute research topic that might be linked in a first instance to the protuberant amount among different population strata. Furthermore, it is known that individuals tend to have a lower quality of life when they live in the presence of high levels of stress. This occurs because their mental and physical health deteriorates due to psychological coercion (de Frias, 2015). Considerably, there are many stress factors that eventually lead to both physiological and psychological disorders that affect the quality of life.

Environmental impact and daily routine issues are also considered evident sources of stress progression. Nowadays, excessive positive and negative triggers such as traffic, deadlines, and first dates are top-ranked in making people stressed. According to a survey conducted by the American Psychological Association in 2018, more than 3,000 respondents pointed out that top stressors are work, money, economy, and health (Alex, 2019). Glanz et al. (2015) have done a study that shows that dissipating actions are required to balance and restore an individual’s equilibrium and address the problem the effective stress management (p.223). Different mechanisms that people experiment with to manage and decrease their stress and agitation are required to cope with their perceived stress momentarily. Meanwhile, new studies have shown that people that poorly react to stress tend to demonstrate more impulsive behavior and tend to become more substance-addicted (Alex, 2019). Hence, the correct psychological perception of issues that lead to elevated stress levels is critical to understanding the ways of managing it.

Context

Smoking is one of the habits that develop as people become unable to control increased stress levels. The conventional wisdom suggests that a person who smokes looks calm and restrained and therefore feels more comfortable with managing potential stress triggers. However, the contextual dependency on nicotine and other addictive substances questions the quality of life and probable connections with high-stress levels (Pina et al., 2018). Furthermore, it is argued that smoking brings an instance of apprehending the true nature of stress relief with the mental tension only for a short period of time. Another view is that different behavioral patterns of individuals eventually lead to the progression of unique coping mechanisms to deal with stress (Ben-Zur, 2019). For instance, the stress generation model of depression suggests that one can impact an individual capability to act adequately and perform general daily functions effectively, as proposed by Hammen (2006). This structure can be seen in the possible relationship between stress and nicotine, drugs or alcohol use, in which the use of substances often leads to higher stress levels.

Rationale

From the psychological perspective, the external pressure caused by the surrounding environment frequently retranslates into mental issues, which consequently leads to the demonstration of harmful human behaviors. In recent literature related to nicotine intake and mental health, mental issues arise more often and contradict the aspect of relating smoking habits to perceived stress (Fluharty et al., 2016). Instead of acknowledging the problem as systematic, people tend to choose timely stress relief, further becoming emotionally vulnerable and demonstrating a non-adaptive behavior. Smoking was explored as an approach to reduce stress symptoms faster; however, it was acknowledged that one does not address the problem that leads to its emerging nature (Mansouri et al., 2019). Steuber and Danner (2006) highlighted that smoking increases the risks of depression but does not reduce stress or negative mood. Furthermore, it was found that people under high levels of perceived stress tend to smoke more cigarettes, which leads to a progressive smoking habit (Finkelstein et al., 2006). Perkins et al. (2008) highlighted that nicotine intake during periods of stress can reduce it even if one occurs for a short period of time. Consequently, the habit of smoking might be considered a psychological dependence rather than the need for nicotine intake and therefore create another daily problem associated with specific diseases (Kwako & Koob, 2017). Hence, this issue will be further investigated and analyzed in this study, with an intention to further contribute to the other scholarly studies and overall topic development.

The proposed methodological approach is to find out possible relations between perceived stress levels and smoking habits among middle-aged adults. To achieve this, an online-based questionnaire survey will be used to analyze the relationships between variables based on descriptive multinomial regression analyses, where cross-tabulation research with a quantitative research method is suggested (Edmonds & Kennedy, 2016). The variables are explored on a predetermined scale and a minimum of hundred participants are required for addressing the validity requirement.

Research Question

The research question is formulated as follows: is there a positive relationship between frequent smoking habits and perceived stress levels among middle-aged adults?

Research Aims

- To investigate if there is a significant relationship between perceived stress levels and amounts of nicotine intake among adults aged between 30 and 65 years.

- To explore if higher levels of nicotine intake allow coping with psychological problems caused by elevated stress indicators for the chosen demographic group.

- To analyze whether different perceived stress levels influence different smoking patterns among the chosen group of participants.

Research Objectives

- To research a non-specific public stratum to examine if different levels of stress in peoples’ lives relate to nicotine intake habits.

- To identify potential behavioral and cultural similarities among different demographic groups with the relationship to their smoking habits caused by stress

- To provide recommendations for addressing the problem of increased nicotine consumption for the demographic groups with the highest risk levels.

Critical Literature Review

Historical Overview

Studying the relationship between stress and nicotine required broad investigation to reveal the effects of smoking on mental health. In order to demonstrate that nicotine consumption can raise stress levels and result in a number of neurological problems, researchers have been studying and gathering data. The historical overview of literature gives an idea of how researchers investigated an arising issue during specific periods of time.

The relationship between nicotine intake and stress levels was actively investigated based on the evaluation of associated environmental and social factors in human lives. Pomerleau (1987) emphasized the need for integration of “behavioral, physiological, and biochemical research” (para. 1) to understand stress and nicotine intake better. The author analyzed recent findings, such as nicotine’s effect on the hypophyseal‐adrenal axis, suggesting that behavioral compensation for inhibited sensitivity due to increased nicotine use during stress exposure can occur. Pomerleau (1987) also indicated that corticosteroids could decrease central nervous system sensibility, which could help with anxiety reduction. However, he also considers that anxiety can be an epiphenomenon in such Considerably, the study provides a sufficient construct to explain how smoking is associated with physiological processes occurring in the human nervous system while avoiding psychological explanations of the underlying triggers and processes.

The scholars also observed behavioral patterns to reveal how stress and nicotine are connected. For instance, Parrott (1999) investigated a possible connection between stress and nicotine, suggesting that nicotine can increase the stress level a worsening one between the individual smoking breaks. Such observation provided a basis to understand how stress relates to nicotine and whether it can exacerbate the stress. The author also points out that nicotine depletion causes increased irritability and tension. However, the study lacks a strong methodological base to conclude that findings are applicable to specific demographic groups and therefore requires more investigation to reveal the connection and to understand the underlying mechanisms.

Another study explored the negative effects of smoking on health, finding both the relationship between stress and nicotine and an association with depressive episodes and neurological issues. Hamer et al. (2010) researched smoking and non-smoking individual behaviors that have no mental illness history based on the Scottish Health Survey sample. It was concluded that high secondhand smoking exposure among people who did not smoke previously was linked to higher odds of psychological distress. Therefore, it could be assumed that for the chosen groups of individuals who demonstrate secondhand smoking behaviors, more psychological issues might arise in the future. Hence, the study proved the influence of nicotine on mental health and a necessity to reduce the percentage of secondhand smokers. However, similarly to the previous example, the study is limited to the particular population of Scottish smokers and therefore is best applied to the specific demographic groups in Scotland only and has limited application in a cultural context.

Overall, the historical perspective suggests that the relationship between nicotine intake and perceived stress levels has been explored both from physiological and psychological levels, with various levels of considering specific details that might be interrelated. However, pursuing the aforementioned research objectives, it is important to explore contemporary studies that are aimed to investigate the psychological aspects of the relationship, arguing that it is important to address the reasons. Finally, given that the research is focused on a rather broad middle-age group of respondents, specific demographic patterns will be attempted to be analyzed further, suggesting future perspectives of the study.

Contemporary Review

It is important to prove the presence of a connection between stress and nicotine to understand how such a connection can impair certain functions in the human brain that eventually cause psychological distress. Kennedy et al. (2019) proposed research that aimed to find out a relation between stress resilience and the development of addictive health behaviors in the middle-aged group. The authors concluded that adolescents with low-stress resistance are more vulnerable to addictions such as nicotine or alcohol use, as well as higher nicotine dependence has been observed. However, the authors also admitted that despite the connection between stress and nicotine having been established, the influence of smoking may vary depending on the period of nicotine consumption and other factors. However, the scope of such influence was insufficiently explored and therefore remains purely theoretical.

Another study investigated how smoking relates to cerebral blood flow (CBF) as it has not been discovered thoughtfully. Cerebral blood flow is a blood supply to the brain for a particular period of time, which leads to the assumption of a negative impact on the central nervous system activity if the CBF process is damaged. Specifically, it was admitted that smoking behavior and arterial spin labeling in regions of the brain lead to dementia. Researchers considered various demographic variables such as status, age of a smoker, time of consumption, and time after quitting and tested the factor relationships among current and former smokers. Elbejjani et al. (2019) discovered that former smokers had “lower CBF in the parietal and occipital lobes, cuneus, precuneus, putamen, and insula” (para. 3), whereas current smokers did not show low CBF. The findings allow concluding that the connection between smoking and CBF exists in areas that are associated with the addictive and cognitive processes, and such influence may vary depending on time and history of smoking exposure. Considerably, study findings could be interpreted as affirmative with relation to the stimulated brain activity to reduce pain and emotional distress, while it also confirms the risks of addiction and potential issues with repetitive manifestations of the stress episodes if an individual quits smoking.

Minimizing the negative effects of chronic nicotine use can aid in the identification of neurobiological substances linked to nicotine dependence. This can be achieved by evaluating people with a brief history of nicotine addiction and by understanding the effects of both short and long periods of smoking exposure on the body. For this purpose, Morris et al. (2016) examined the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to the Trier Social Stress Test among individuals with a short history of nicotine dependence. Researchers looked at behavioral indicators of nicotine dependency and withdrawal, salivary biomarkers in reaction to the test, and signs of recent smoking, such as carbon monoxide in the breath and salivary cotinine (Morris et al., 2016). According to the study, those with less nicotine addiction had higher cortisol reactions to the stresses. In contrast, those with higher levels of nicotine dependence did not react to the stressor with variations in cortisol. Consequently, the stress response system can be impaired among individuals with a more severe level of dependency, which proves the need to find ways to prevent smoking behavior among individuals with a short period of smoking consumption, since the psychological response will eventually result in addiction that will be not related to the stress factors and eventually transformed into a daily habit.

The relationship between nicotine consumption and stress as well as other addictions like alcohol can be explained by the underlying brain process. Ostroumov and Dani (2018) aimed to discover how stress and nicotine smoking can become a hazard factor for alcoholism, stating that certain mental activities are similar to appreciating the consumption of substances to reduce stress based on past experiences. Through the release of signaling molecules that affect synaptic transmission, stress “modulates alcohol-evoked plasticity,” according to researchers (Ostroumov & Dani, 2018, para. 1). Unfortunately, the study avoids analyzing specific factors such as past life events that might lead to elevated consumption of both alcohol and nicotine, such as replication of behaviors of others during adolescence, stressful family situations, and violence.

Another study explored the problem of shifting smoking preferences from regions with high income to middle- and low-income countries. Stubbs et al. (2017) used the Perceived Stress Scale and applied a multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the change in smoking habits among respondents around the world, stratifying those per continent. Based on the results of a cross-sectional, community-based study, Stubbs et al. (2017) concluded that increased stress associated with smoking was observed in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, while such conclusions were not evident for the European countries. Reapplying these findings against socioeconomic and societal behaviors, it is evident that the culture of smoking in the developed world is continuously eradicated, while the continents with the higher number of developing countries pursue smoking habits as a matter of managing stressful economic times and social wellbeing.

Finally, it is worth considering the recent effect of COVID-19 as a stressful factor that might eventually have an impact on smoking habits. Recent research conducted among Dutch smokers in May 2020, after the six weeks past the initially reported number of peak death records in the country, has shown that slightly more than 14% of smokers were intaking less nicotine, while more than 18% of smokers concluded otherwise (Bommele et al., 2020). The authors explained such tendency as a different perception of the pandemic risks, where some participants were emotionally stimulated to smoke more because of the boredom and restrictions, while others were afraid of contracting the disease because of anticipated health conditions related to smoking (Bommele et al., 2020). Considerably, the study findings imply that there is a significant need to develop strategies for smoking cessation service provision to improve healthy habits in pandemic times.

Theoretical Framework

The issues of stress management and related comorbidities have been actively explored by both physicians and psychology practitioners. The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping Theory by Lazarus & Folkman (1984, cited by Schmidt, 2017) highlights that smoking may seize the role of a strong cope way in everyday lives for people who are exposed to the continuous stress factors. Furthermore, the theory is focused on two categories of individuals, such as people who have either a problem-focused coping mechanism or an emotion-focused one. The first group tends to behave more logically and tries to identify and control the influence of the stress source. Alternatively, the second group prefers to choose a temporary stress relief mechanism, as well as transfer the stress into another conditional realm that might lead to even higher levels of emotional instability (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, cited by Mansouri et al., 2019).

Furthermore, theoretical studies suggest that excessive emotional pressure and interpersonal conflicts might lead to intensive stress formation among individuals based on their personality profiles. Wiggert et al. (2016) observed that smoking tension in such cases is “related to multiplied strain-related urges to smoke for remedy” (p. 8). Another perspective relates to stress sensitivity, which is considered to be a primary factor that contributes to the development of mood disorders. As nicotine and stress can cause long-lasting cellular changes within the dopamine system, Morel et al. (2018) sought to demonstrate that nicotine exposure increases stress sensitivity. Also, because the majority of people report feeling irritable, anxious, and depressed, researchers are curious to learn about the physical impacts of drug withdrawal. (Morel et al., 2018). Hence, both studies inform the importance of mood as a construct that could be an initial stressor for one-time smoking efforts while further becoming a consecutive factor for stress management and control.

Previous analysis suggests that nicotine can be associated with stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms that can lead to mental issues; however, the relationship between the substance and triggers is complex. Despite the fact that nicotine can increase the possibility of depression development, adverse effects are observed as depression can also lead to smoking addiction. Moreover, drug withdrawal episodes are associated with people who already experience depression, which can complicate the process of quitting for an individual. Nicotine intake positively relates to anxiety and depression, which was particularly supported by the research conducted by Fluharty et al. (2016). Moreover, depressive individuals represent a higher nicotine-dependent demographic group and encounter more issues in selecting smoking cessation ways. Furthermore, these individuals experience difficulties in quitting smoking as nicotine urges them to be in-take (Reid & Ledgerwood, 2015). Yet, the aforementioned studies relate more to depression and anxiety issues like mental illness other than daily stressors triggers.

Specific addiction types and their correlation with stress were explored in several recent studies that might further enhance the theoretical background, for instance, the exploratory research by Kwako and Koob (2017) and Robles (2019). Furthermore, the study by Glanz et al. (2015) explains that an individual’s physical and psychological health needs to be improved through a coping mechanism that restores equilibrium between the stress level and irregular interference on the environmental level (p.223). Hence, the presented theoretical constructs require further validation and formulation since the associations between critical stress factors and elevated nicotine intake are vast and are not appropriately classified and structured through a single behavioral model.

The context for the Study

Given that nicotine causes worldwide health and economic issues, a more comprehensive understanding of the connection between stress and nicotine is helpful. Addiction is a chronic psychiatric disease, and stress is one of the leading factors in its progression. Understanding the relationship between stress and nicotine is also critical due to the necessity to implement adequate problem management strategies and prevent the risks of negative health consequences.

Health problems associated with smoking create not only physical but also mental issues, which affect the quality of life. A report by the Action on Smoking and Health organization explains that smoking is the primary reason for life expectancies by 10 to 20 lower compared to the general population (Burki, 2016). Because of the relationship between stress, nicotine, and mental issues, as well as the complexity of the subject, the research revealing the interconnectivity between the model components is critical. The relationship between nicotine intake and mental illness proves the need to investigate an issue among specific age groups to prevent potential health harm caused by smoking.

Based on the past studies, it is important to conduct a deeper investigation to obtain information that helps to investigate an issue and develop a plan for problem management, as well as find new ways of dealing with the consequences of nicotine consumption. In order to stop the tobacco epidemic in the United States, researchers concentrate on creating methods to stop teen and young adult use because middle-aged people suffer negative consequences. Zhou et al. (2019) suggested addressing behavioral health challenges and increasing access to mental health services since demographically, it applies to more than one-half of adolescents and young adults in the region. Furthermore, tobacco use may be suggested by pre-existing mental disorders such as anxiety. Lasser et al. (2000) found that 55 percent of individuals exposed to the risks of having anxiety diseases are regular smokers. Alternatively, Torres and O’Dell (2016) discovered that females are consuming more tobacco products, which is associated with various factors.

Firstly, women are more susceptible to anxiety disorders than men, which contributes to higher smoking addiction. Secondly, females tend to associate continuous tobacco consumption with anxiety-reducing effects, which prevents them from quitting the habit and leads to elevated risks of comorbidity affect progression. Finally, females experience more stress during the smoking cessation process compared to males. Hence, the listed factors provide a basis to conclude that stress contributes not only to the initiation of tobacco use but also to the relapse during abstinence, which means that the process of quitting can be more challenging for females (Torres & O’Dell, 2016). Furthermore, 30 percent of all cigarette consumption in the US is allocated to the smoke addicts that are also diagnosed with anxiety disease (Grant et al., 2004). The above studies are compatible with the other research efforts, which demonstrate that rates of anxiety are higher among smoking individuals compared to non-smokers (Lawrance et al., 2005; McClave et al., 2009).

Apart from the biological factors that influence the intention of smoking, certain social factors can contribute to the development of relevant behaviors. Jahnel et al. (2019) explored how socioeconomic disadvantages induce indirect effects on smoking caused by daily stress. The social parameter was measured by the variables of educational achievement, income, race, and the average amount of cigarettes consumed daily. Researchers used Ecological Momentary Assessment methods for stress measurement evaluation. The experiment showed a significant increase in stress exposure among lower-educated African American smokers, which led to an increase in tobacco consumption. Similarly, the Advances in Life Course Research study examined a cohort of students to discover various reasons for individuals to initiate, continue, or quit smoking and discover how social connections can influence relevant behavioral styles and identified the importance of social connections that contribute to initiating smoking habits (Thomeer et al., 2019). Therefore, the behavioral mechanism of nicotine addiction is also essential, and one should be able to see factors related not only to the initiation of smoking and stress but also to other related factors such as daily stressors which might lead people to smoke.

The relationship between stress and smoking habits is an important topic for understanding behavioral motivations as well. Mauro et al. (2015) suggested more research into the subject as high smoking tendencies by midlife adults might indicate the presence of supposed behavioral patterns among individuals of similar age. Moreover, the same is considered a foundation for other studies such as the one by de Frias and Whyne (2015), who stated that there is an inverse correlation between age and mental health indicators. For instance, it was admitted that if “frequent prescription/other drug use coping is associated with poor self-rated health two years later,” it might mean that there is an existence of a gradual decline in health among individuals of similar age (Mauro et al., 2015, p.6). Hence, it means that studies that focus on midlife adults are necessary as they might be considered as a target group that conceals the potential for health deterioration other than health improvement.

Specific studies also indicated the difference in stress factors and their manifestation among genders. For instance, Kotlyar et al. (2017) capitalized on the gender-adherence reflection of “the combination of stress and smoking” (p. 6), where higher blood pressure after encountering stressors was observed among males rather than females. On the contrary, Lawless et al. (2015) emphasized further, claiming that men report lower stress levels with less intense withdrawal symptoms. Moreover, female smoking habits are different than those reported by males, with the former included in a group with higher addiction risks (Torres & O’Dell, 2016). Hence, it is reasonable concluding that depending on gender, middle-aged adults demonstrate polar addictive behaviors related to managing their self-management and health-focused habits.

To summarize, the study points out that nicotine intake and related issues create an economic burden and significant concern for health institutions. Research that reveals the connection between the components such as stress and nicotine is crucial to get a full image of the issue to develop effective strategies toward its eradication or at least potential ways to diminish it. Healthcare providers and researchers should take a closer look at revealing the connection between daily stress factors, nicotine addiction, and mental illness as it remains unclear whether addiction causes psychological issues or vice versa. Understanding underlying mechanisms, examining highly exposed demographic groups, and investigating the issue further can contribute to the development of a healthier environment.

Finally, the proposed research will further investigate the correlation between nicotine intake and stress among midlife adults aged 30 to 65 years. It is known that midlife individuals constitute a highly sensitive group because of the presence of legal drugs available and eventually used to cope with perceived stress levels. However, it was also demonstrated through the literature review that drug overuse in stressful life situations compromises the quality of life for the specified group of individuals (Mauro et al., 2015). Hence, primary research intervention is required to explore specific stress factors that contribute to increasing or decreasing smoking addiction for the chosen age group and identify the strength of the relationship between perceived stress levels and nicotine intake, eventually discussing relevant coping techniques.

Research Methodology

Research Design

To fulfill research objectives, a quantitative research approach has been chosen. It uses numerical and statistical measurements as a basis and was deployed using a pre-established survey (Babbie, 2010). Taking into consideration individual life conditions and the assessment of the potential relationship between smoking habits and stress on people’s life proposed, the quantitative inquiry might assist with better problem insights and psychological understanding. Furthermore, the quantitative surveying approach may simplify the prevailing, self-conscious tendencies between different population segments (Edmonds & Kennedy, 2016; Nardi, 2018). Rooney and Evans (2018) stated that the requirement for investigations might be based on setting out connections that might exist among different variables, such as the development of smoking addiction as a response to stress-inducing life experiences. Moreover, the quantitative surveying method best fits the investigations that are settled among different population strata (Percy et al., 2015). This type of theoretical framework is best actualized through the terms “reliability, validity, replicability, and generalizability” (Brown, 2015, p.26; McBride, 2020). Hence, the choice of quantitative method reassures the idea of scoping the study to the smaller research sample, while further allowing using one for applying to the larger population and generalization to the subject of research.

Sample Size and Sampling Technique

For the study, participants were recruited through social media channels and freely consented to taking the survey. For the responders to answer the research, they have to read and accept the “Participants Information Sheet” (PIS) (see Appendix A). The minimum acceptable age is 18 years: however, some participants were excluded because of the initially communicated age limits between 30 and 65 years old. Overall, 116 respondents successfully participated and provided their responses; however, 13 responses were excluded from the study because of the missing values to avoid biased interpretations. Bell et al. (2018) suggest that the averaging method could be used to address redundancies of such kind; however, the nature of questions developed appeared to be not applicable. Hence, dropping such responses was the best approach to reduce the margin of error and approach more realistic results to meet the intended research aims and objectives.

Scale and Measurement

The survey questionnaire included three distinct parts, such as demographics, perceived stress scale (PSS), and smoking behavior. The first and third parts were designed based on the categorical approach. The demographic variables explored in the first section of the survey are the age group, gender, marital status, education level, and participants’ origin. The design of the second survey section was aimed to investigate perceived stress and is based on the five-point Likert scale questionnaire ranging the answers from never to very often.

The pre-designed questionnaire for the survey is provided in Appendix B. It was informed by the methodological approaches used in two studies. The first is Cohen’s (2019) “Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),” a questionnaire aimed to investigate the smoking habits of the participants. Historically, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was designed to investigate the extent to which regular life status was appraised as stressful (Tavolacci et al., 2013). For the study purposes, the version that features 10 questions have been chosen. Each item was scored on a scale from 0 (zero) to 4 (four), and the score of items 4, 5, 7, and 8 were reversed. Higher scores corresponded to higher perceived stress levels in a linear relationship. Since PSS is not a diagnostic instrument, there were no cut-offs to determine stressed individuals; hence, only the between-group comparison was applied. (Tavolacci et al., 2013). The perceived stress levels were evaluated by summing up responses to all questions, ranging between 0 to 40, with the higher values indicating higher perceived stress levels. Specifically, the following distribution principle was applied:

Data Collection

The primary data for the research has been collected from the survey distributed online. The secondary data has been collected from journal articles and other authentic sources in line with topics and ideas that meet previously specified research questions and objectives (Zikmun et al., 2013). For the current study, the focus is made on the importance of having robust primary data considering the need of validating previous empirical findings outlined in the past literature and further contribute to the research efforts and practical interventions in the area of psychology.

Procedures

The procedure used to investigate the research question relied on the collection of data through a pre-established survey where participants’ age, marital status, gender, education level, place of birth, perceived stress level, and smoking habits were probed. Rooney and Evans (2018) affirmed that information such as age and marital status allows drawing on the effect of individual behavior changes though apperceiving additional potential links between specific variables. The survey was available online and was distributed using social media for a limited timeframe. After the survey was administered and data was collected, the researcher engaged in categorizing and appraising the collected data, making conclusions based on the pre-designed analysis plan (Nestor & Schutt, 2018). Finally, analytical results were documented based on statistical information and data-driven conclusions.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis requires using specific tools and methods to provide meaningful data interpretation. For the current study, the data was collected online using Qualtrics software and further transferred to SPSS software for future analysis. It was initially considered that the data could be analyzed using either multiple or multinomial regression methods. The basic difference between both empirical methods is that multiple regression is used on continuous variables; however, when dealing with categorical variables, the approach’s effectiveness is not justified (Batool and Batool, 2018). Considerably, multinomial regression, also known as logistics regression, is a more appropriate technique for the empirical investigation when the dependent variable is a categorical one. Applying a statistical procedure for the different variable types is considered to be the most effective way for the research to collect the data based on the need of having better data representation.

Ethical Considerations

A self-reflective questionnaire was used as the research instrument, assuming that no participant-researcher contact is required. Nevertheless, privacy-related ethical concerns were observed and addressed as properly, proving the participants’ full guarantee of confidentiality (Nestor & Schutt, 2018; BPS, 2017). Furthermore, the concern about tobacco, alcohol, and drugs as substances that lead to addiction was considered, which might be eventually seen as an unethical inquiry from the perspective of personal habits and unnecessary life intervention. Hence, it should be considered when analyzing the perceived stress levels and smoking dependence through the anonymization of participants on the results’ publication (Nestor & Schutt, 2018; BPS, 2014). Additional measures such as securing the research data and non-distributing its outputs were considered from the safeguarding perspective to avoid social shaming and challenging personal habits if the tendency towards addiction might be eventually unveiled (Rudolph et al., 2016). Finally, participants were not required to provide individual information such as name and email address to maintain anonymity and avoid potential constraints on further requests related to the concerns highlighted above.

Validity and Credibility

The validity of the data will be tested using statistical instruments available in SPSS, such as measuring Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The importance of introducing validity (reliability) testing as a part of the research methodology is important to ensure that the data collected through the investigation process is statistically consistent and self-explanatory, meaning that the chosen sample is significant to address the problems stated in the research objectives. Furthermore, validity needs are explained as those that require having the raw data collected and securely stored to verify research information (Brown, 2015). The credibility aspect was addressed by using the pre-developed methodologies for psychological survey analyses justified in the past studies, such as the focus on PSS as a guiding instrument for customizing and generalizing behavioral patterns expressed by the research participants. Finally, at the different stages of the study development, it was verified through intermediate checks and progress reports to ensure that credible and updated data and information is used for both primary and secondary research inquiries.

Data Analysis and Discussion

Demographic Analysis

The total number of participants considered for the analysis is 116 samples; however, some responses were excluded because of the data validity concerns. The demographic summary is provided in Table 1 and includes the information based on the refined sample collected from 103 participants based on the specific factors explored per individual. In terms of the age factor, 60.2% of the participants were between the age of 30 – 40 years, 30.1% of the individuals were between 41 – 50 years, 8.7% of the participants were between 51 – 60 years, and 1% of the participants were between 61 – 67 years. Hence, this indicates that the majority of the participants were between 30 – 40 years. For the age factor, there were 41.7% male respondents and 58.3% of female respondents. In terms of marital status, there are 23.3% of those who never married, 65% of the married individuals, 7.8% of respondents who were separated, and 3.9% had divorced. Finally, for the educational status, there were 4.9% of participants held a high school degree, 11.7% held some college or no degree, 20.4% held an associate degree, 45.6% of the respondents held bachelor’s degree, and 17.5% of participants having a graduate degree.

Cross-tabulation

Cross-tabulation is a statistical technique used for discussing and interpreting the association of two categorical variables in a single table. For instance, the categories of one variable are presented in a column, whereas the other variable’s categories are represented in a row (Wildemuth, 2016). The significance of the variables is measured through the chi-square test, which relates to the procedure of independence analysis. While referring to the chi-square test of cross-tabulation, it has been measured through Pearson chi-square, which helped to evaluate the significance of the relationship between the variables. The chosen value for the statistical significance measurement was chosen at 0.10 or 10%. Therefore, if the p-value on Pearson chi-square is computed as less than 0.1, it indicates the presence of a significant data association. The cross-tabulation is conducted by evaluating the age of the individuals with respect to the variables related to smoking behavior.

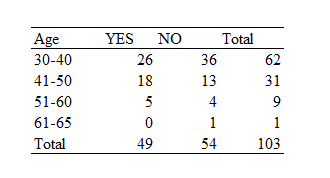

Tables 5 and 6 show the cross-tabulation between ages and smoking and confirm among the chosen population, there are 49 smokers and 54 non-smokers. The majority of identified smokers are in the 41-50 age group, with the approximate diapason of 20 to 40 individuals. The Pearson chi-square reports the computed p-value of 0.348, which is above the used 0.10 threshold. Hence, it confirms that there is no difference between the age and smoking parameters used in the test for independence. Moreover, it also indicates that the smoking habit of individuals does not differ as people are aging.

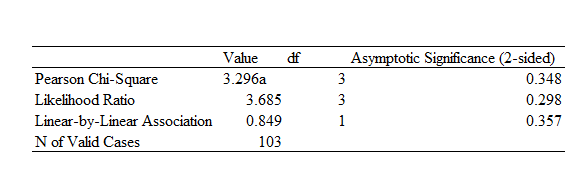

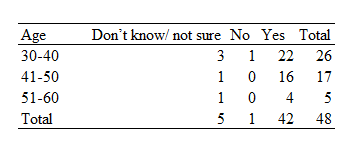

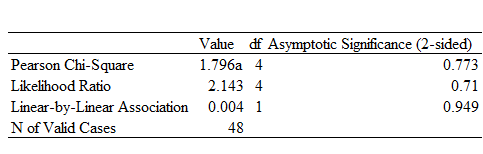

Table 7 and 8 is a cross-tab computation between the age group and their perception regarding stress triggering smoke. It is identified that the majority of the people have considered that stress triggers individuals to smoke or intake nicotine, as 87.5% of the participants have indicated. While 10.4% were not sure as it causes individuals to intake nicotine while 2.1% has indicated as no. The majority of the participants who agree that stress triggers smoke is the age group of 30 – 40 and 41 – 50. While referring to the Pearson chi-square, its p-value is computed as 0.773, which is higher than the p-value. Therefore, it can be indicated that the perception of stress triggering smoking and age are not significantly different. In other words, the perception of stress triggering smoke is not associated with the age of the individuals.

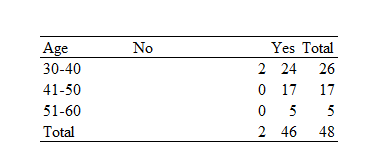

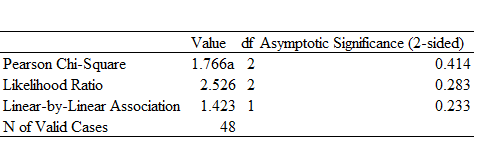

Table 9 and 10 represents the cross-tabulation of age and perception of smoking in terms of relaxed feeling. While referring to table 9, it is clearly identified that the majority of the respondents (95.83%) have indicated that smoking provides a relaxed feeling, whereas 4.17% of the participants have indicated that it does not provide a relaxing experience. In terms of age group, the largest group to agree with smoking providing a relaxing experience is 51-60. While referring to the Pearson Chi-square in Table 10, the significance value is computed as 0.414, which is higher than the threshold value. Hence, this indicates there is no association between age and the relaxed feeling experienced by smoking. It also shows the perception of the individual in terms of age does not differ with respect to the relaxed feeling of smoking.

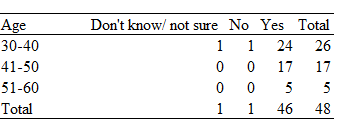

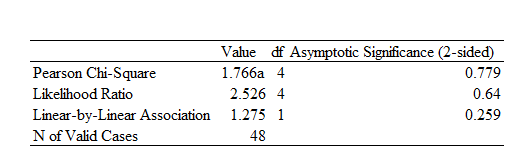

Table 11 and 12 is the computation of cross-tabulation between the age and the statement that smoking causes a decrease in stress perception at the time of smoke. While reflecting on table 11, the majority of the participants stated that smoking decreases stress, whereas only one participant was unsure while one of them had not agreed. While reflecting on the age group, the majority of the participants who had agreed that smoking decreases stress were 41-50 and 51-60. While referring to the chi-square value, the Pearson chi-square was computed as 0.44, which was > 0.10. Hence, the age group and the perception regarding smoking decreasing stress are not significantly associated with each other.

Multinomial Regression analysis

The statistical technique, which is referred to as multinomial regression, is reflected in linking the nominal dependent construct with the presence of one or more than one independent construct (Sun et al., 2017). It is also an effective method for determining the consistency of the model that is used in the study while also identifying which variables chosen have an excellent fit or not. The multinomial regression is applied on the data set where the independent variable or regressor of the study is the sum score of perceived stress, whereas the regressand identifies in the study are the nicotine intake, decreasing stress level, and experiencing relaxation. Thus, there are three models that are involved in the study where the multinomial regression is applied for evaluating the effects of stress on nicotine intake.

Model 1

The first model of the study is emphasized evaluating the effects of stress on causing the trigger to smoke. Therefore, the model is subjected to multinomial regression analysis, with the regressand being the smoking trigger and the independent variable being the total of the stress scores.

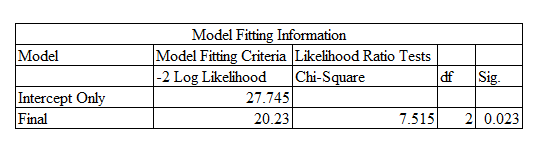

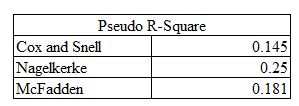

Table 13 represents the model fitting information where only the significance value is evaluated and interpreted. As discussed above, the threshold value that is recognized for the study is 10% or 0.10. On this basis, the significance value as shown in the above table is 0.023, which is < 0.10; hence, this indicates that the first model developed from the multinomial regression analysis is significant and excellently fits. It also signifies that the stress of the respondents triggers having a smoke.

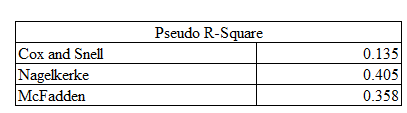

Table 14 presents the value of pseudo-R-square, which is connected with comparing similar data for predicting the same outcome. The higher value of pseudo-R-square indicates that the model is able to predict smoking in a better manner. While referring to Cox and Snell, the model is computed as 14.5%, whereas Nagelkerke is computed as 25%, and lastly, with respect to McFadden, the R-square is computed as 18.1%, which indicates that the overall sum of stress is explaining 18.1% of triggering of smoke.

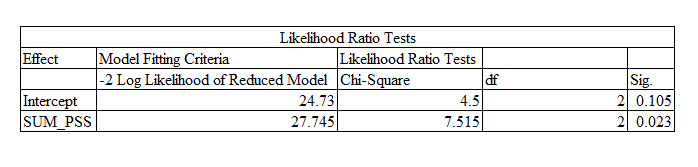

Table 15 indicates the likelihood ratio test of the multinomial regression, where it shows the significance of the variables associated with others. The threshold value is indicated as 0.10, where the values under this are considered to be significant. While referring to Table 15, the sum of the perceived stress score has a significance value of 0.023, which is low than 0.10; hence, it can be indicated that the variable has a significant influence on triggering smoking.

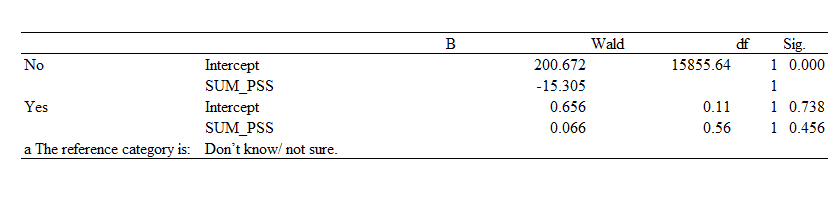

The parameter estimates for the claim that stress causes smoking are shown in Table 16. The category variable in this model is ‘Don’t know/not sure.’ The significance threshold that is considered for the parameter estimates is 5% or 0.05. While referring to the category ‘no,’ it is found to have a significant influence due to the value being 0.000, whereas in the category ‘yes,’ the variable stress is found to have an insignificant influence where the coefficient is 0.738. This indicates that smoking is found to be affecting the stress levels negatively in the perception of those who answered in assertion as compared to those who do not consider it.

Model 2

The second model of the study is emphasized whether smoking has an impact on providing a relaxation experience among stressed individuals. The independent variable is the sum of stress scores, while the regressand is the relaxation experience.

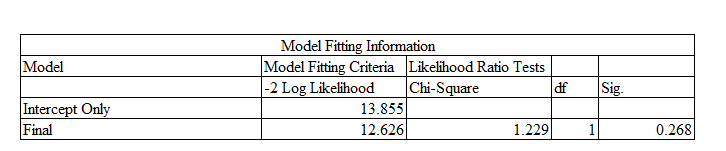

Table 17 reflects the model fitting information where the significance value is computed as 0.268, which is above 0.10 or 10%. Hence, this indicates that the second model is not significant and excellently fit.

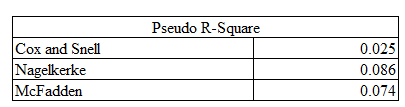

Table 18 represents the Pseudo R-square for the second model of the study where the Cox and Snell, the model is computed as 2.5%, in terms of Nagelkerke, R-square is computed as 8.06%, and finally, the R-square for McFadden is calculated as 7.4% which suggests that stress as a whole is explaining 7.4% of relaxation from the smoke.

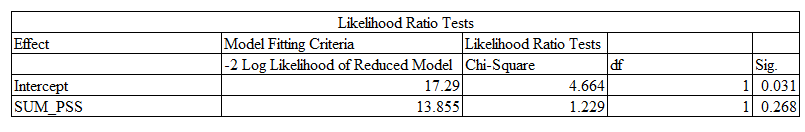

Table 19 highlights the likelihood ratio test for model 2, where the significance of the variables is indicated. While referring to the outcome, it is found that the significance value of SUM_PSS is 0.268, which is above 0.10; therefore, this can be illustrated that the SUM_PSS has an insignificant influence on causing relaxation experience the smoke.

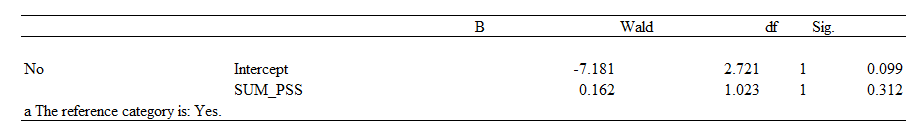

Table 20 represents the parameter estimated for the stated as to whether smoking provides a relaxation experience where the reference category variable is ‘‘yes.’ Because the value is more than 0.05, the category “no” is deemed to be insignificant. Hence, it can be indicated that smoking does not provide a relaxation experience for stressed individuals.

Model 3

The third model of the multinomial regression was focused on determining whether smoking reduces the perceived stress level.

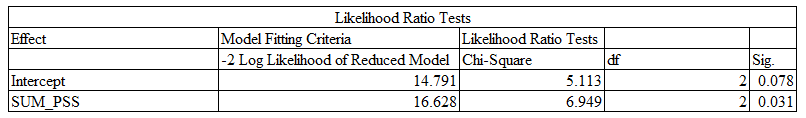

Table 21 indicates the model fitting information for the third model of the study in which its significance is analyzed and discussed. With respect to the significant value of the model, it is computed as 0.031, which is < 0.1; therefore, it can be indicated that the third model of the study is significant and excellently fit.

Table 22 indicates the pseudo-R-square for the third model for evaluating the variance of the regressors on the regressand. The Cox and Snell R-square is computed as 13.5, whereas Nagelkerke R-square is computed as 40.5%, and lastly McFadden is computed as 35.8%, which indicates the variance of the decline of stress is explained by smoking by 30.8%.

Table 23 explains the likelihood ratio text regarding the multinomial regression, which determines the significance of the variables with one another. The threshold value identified for the Likelihood ratio test is 0.1 or 10%. In this perspective, the significance of SUM_PSS is computed as 0.031, which is lower than the threshold value. This signifies that the SUM_PSS has a significant influence on causing a decline in the perceived stress level from the smoke.

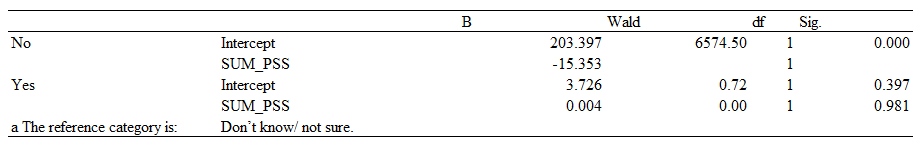

Table 24 represents the parameter estimates for the statement as to whether smoking causes the perceived stress level to decline. This model’s category variable is “Don’t know/not sure.” For the parameter estimations, the significance level taken into account is 5%, or 0.05. The score of 0.981, which is greater than 0.05, indicates that the category “yes” has a considerable impact. On the contrary, in the category ‘no,’ the variable SUM_PSS is discovered to have a noteworthy impact since the value is 0.00, where the coefficient is -15.535. This indicates the one unit increase of stress would result in causing a shift from ‘no’ to ‘don’t know/not sure.’ It can similarly indicate that the increase in stress would cause the category ‘no’ to shift to ‘don’t know/not sure.’

Discussion

Stress is characterized by the symptoms of depression and anxiety, which has been a major focus of research. Regardless of smoking being injurious to health, it is identified that many individuals smoke to reduce their stress and tension. The majority of smokers wish to stop the habit; however, they are unable to do it due to their addiction (Siegel et al., 2017). Moreover, Albert et al.’s (2017) study has indicated that the majority of the individuals who smoke for releasing their stress and anxiety are middle- and older-aged individuals. Thus, the study was mainly conducted to determine whether stress causes nicotine intake among middle-aged individuals. The researcher has adopted the questionnaire survey, which was mainly distributed among the aged individuals. A cross-tabulation was conducted, which revealed that the intake of smoking does not differ among the aged individuals. On the other hand, the study conducted by Mansouri et al. (2019) has indicated that the smoking habits of the aged group are different from each other.

Thus, the results of the research contradict the study of Mansouri et al. (2019). While referring to the main results of multinomial regression analysis, it was identified that the stress significantly caused the middle-aged individuals to smoke as it helped in reducing their stress and also encouraged the individual to smoke to cope with their high level of stress. Similarly, the study conducted by Lawless et al. (2015) has highlighted that stress is significantly declined among smokers leading to a withdrawal of a few psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and tension. With respect to model 2 of the multinomial regression, it was identified that smoking does not provide a relaxation experience to the middle age people due to insignificant results. While comparing the results of model 2 with the study of Choi (2015), it was identified that smoking provides a relaxation experience while also relieving the stress of the individual. Hence, the results of the study contradict the study of Choi (2015). Overall, it is found that the stress among middle-aged individuals triggers them to smoke for the purpose of reducing their perceived stress level.

Summary

The section was particularly focused on conducting the data analysis and discussion with respect to identifying the effect of stress on nicotine intake among middle-aged people. The study incorporates a questionnaire survey distributed among the participants, and further statistical techniques were applied to the dataset. While reflecting the dataset, the majority of the participants were female, and in terms of age, the participants were 30 and above, which signifies that the data is collected from middle-aged people. The cross-tabulation is conducted where the demographic variable age is compared with the variable smoking. It was found that a participant’s smoking habit varies with their age, meaning that the older aged people did not smoke. Additionally, three models were assessed using the multinomial regression technique. The first model was used to determine how stress influenced middle-aged people’s decision to smoke. The results of the study have indicated that stress was a major driver for influencing smoking and nicotine intake. The results of the second model’s reflection on whether smoking contributes to participants’ relaxation were insignificant, indicating that smoking did not induce relaxation. When examining whether smoking can lower perceived stress levels, the third model was highlighted and found to be significant.

Conclusion

From the following report, it has been concluded that stress has been characterized as one of the symptoms of smoking, and another is anxiety. These two aspects have been regarded as the main concern in the present research. There is no doubt that smoking is injurious to health, but other factors have also been identified, which cause this habit. In the section on methodology, data collection procedures in this study were adopted from the survey. Certain variables have been considered in which data was collected, and those variables are marital status, age, educational level, gender, etc. In terms of age demographics, it has been observed that the highest percentage has been found in the range of 30 to 40 years of frequency, whereas 31 percent of those persons are in the range of 41 to 50. Similarly, analysis has been performed in the category of male and female; it has been noticed that females are involved more as compared to males. From the sample size of 103, there were 60 females who answered the survey, whereas the ratio of the male was equal to 43. In this way, married persons and individuals holding bachelor’s degrees are prominent in terms of marital status and education, respectively.

Following these analyses, cross-tabulation techniques were also applied in order to observe the facts and figures more closely. Age and currently smoke analyses are performed, and it has been observed that results vary differently as compared to previous analyses. Those respondents who fell in the length of 30 to 40 years old were 75, and among those, there were only 49 participants who do not smoke and the remaining 26 persons who smoke. In this way, it has also been observed that there were 31 persons who fell in the range of 41 to 50, and there were 18 persons who smoke.

Other statistical techniques used in this regard are multi regression analysis, and three models have been applied in this regard. The first model was related to emphasizing on evaluating the effects of stress on causing triggers in terms of smoking, and the model was found to be significant at 10%. In this way, it indicates that there is a significant effect of stress associated with smoking habits. The second model was to study the impact of smoking experience on individuals’ stress, and this model was not found to be significant at 10% and does not fit on the data. In other words, it reflects that there is no significant impact of smoking experience on individual stress. However, the 3rd model was applied in order to determine the effect of smoking in order to the perceived stress level. This model significantly fit on the data at 10% and was computed as 50.1% of R-Squared value, which means that the research can rely on this model. Overall, the study shows that responders are liked to use emotional-focused coping mechanisms, finding out fast and not a lasting solutions to their perceived stress levels. Smoking is proven to be one of it.

Limitations and Recommendations

The research results might be considered in the context of its limitations. Data collection was available through social media for a brief period of time; the sample size can be considered relatively small, which could possibly interfere with the detection of the correct strength amidst smoking habits and stress levels. Thus, the sample was sufficient to determine the line that stressed people follow to cope with it; stress and nicotine intake have a significant relation. Additionally, the sample was unevenly split between males and females, which was combined to compose one single greater group. Furthermore, it is important to note that analyses were also considered between different perceived stress levels, which brought the sample to a smaller sample size, which could also compromise the final results.

Confirming a connection between frequent smoking and individuals’ heightened stress levels can provide further researchers an insight into designing new studies that aim to alternate stress-management techniques. Future investigations into the connection between smoking habits and stress could also bring up different benefits to scientific comprehension and treatment. Treatments sketched to heighten mindfulness, relaxation, and stress tolerance might be helpful for people who encounter high-stress levels and currently chose smoking as their coping mechanism.

References

Albert, M.A., Durazo, E.M., Slopen, N., Zaslavsky, A.M., Buring, J.E., Silva, T., Chasman, D. and Williams, D.R., 2017. Cumulative psychological stress and cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and older women: Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. American heart journal, 192, 1-12.

Alex, B. (2019). Stress. Discover, 40(6), 54-57. Web.

Babbie, Earl R. (2010). The Practice of Social Research. 12th ed. Wadsworth Cengage.

Batool, S.A. and Batool, S.S., 2018. Ordered Logit Regression Models of Women’s Empowerment with Comparison to Ordinary Least Square Models. Paradigms, 12(2), 139-146.

Bell, E., Bryman, A. and Harley, B., 2018. Business research methods. Oxford university press.

Ben-Zur, H. (2019). Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 1-4.

Biala, G., Pekala, K., Boguszewska-Czubara, A., Michalak, A., Kruk-Slomka, M., Grot, K., & Budzynska, B. (2018). Behavioral and biochemical impact of chronic unpredictable mild stress on the acquisition of nicotine conditioned place preference in rats. Molecular neurobiology, 55(4), 3270-3289.

Boku, S., Nakagawa, S., Toda, H., & Hishimoto, A. (2018). Neural basis of major depressive disorder: beyond monoamine hypothesis. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 72(1), 3-12.

Bommele, J., Hopman, P., Hipple Walters, B., Geboers, C., Croes, E., Fong, G.T., Quah, A.C.K., & Willemsen, M. (2020). The double-edged relationship between COVID-19 stress and smoking: Implications for smoking cessation. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 18, 63. Web.

Brown, J. D. (2015). Characteristics of sound quantitative research. Shiken, 19(2), 24-27. Web.

Burki, T. K. (2016). Smoking and mental health. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 4(6), 437.

Choi, D., Ota, S. and Watanuki, S., 2015. Does cigarette smoking relieve stress? Evidence from the event-related potential (ERP). International Journal of Psychophysiology, 98(3), pp.470-476

Cohen, S. (2019). Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Science. https://midss.ie

de Frias, C. M., & Whyne, E. (2015). Stress on health-related quality of life in older adults: The protective nature of mindfulness. Aging & Mental Health, 19(3), 201-206. Web.

Edmonds, W. A., & Kennedy, T. D. (2016). An applied guide to research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Elbejjani, M., Auer, R., Dolui, S., Jacobs Jr, D. R., Haight, T., Goff Jr, D. C.,… & Launer, L. J. (2019). Cigarette smoking and cerebral blood flow in a cohort of middle-aged adults. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 39(7), 1247-1257.

Finkelstein, D. M., Kubzansky, L. D., Goodman, E. (2006). Social status, stress, and adolescent smoking. J Adolesc Health. 39(5), 678-85. Web.

Fluharty, M., Taylor, A. E., Grabski, M., & Munafo, M. R. (2016). The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(1), 3-13. Web.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath K. (2015). Stress, Coping and Health Behaviour. In J. W. & S. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5, 223-242. Jossey-Bass

Grant, B. F., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Chou, S. P., Ruan, J., Pickering, R. P. (2004). Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 362–368.

Hamer, M., Stamatakis, E., & Batty, G. D. (2010). Objectively assessed secondhand smoke exposure and mental health in adults: cross-sectional and prospective evidence from the Scottish Health Survey. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(8), 850-855.

Hammen, C. (2006). Stress generation in depression reflection on origins, research, and future direction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(9), 1065 – 1082.

Hwang, J., & Yun, Z. S. (2015). Mechanism of psychological distress-driven smoking addiction behavior. Journal of Business Research, 68(10), 2189-2197. Web.

Jahnel, T., Ferguson, S. G., Shiffman, S., & Schüz, B. (2019). Daily stress as a link between disadvantage and smoking: an ecological momentary assessment study. BMC public health, 19(1), 1284.

Kennedy, B., Chen, R., Fang, F., Valdimarsdottir, U., Montgomery, S., Larsson, H., & Fall, K. (2019). Low stress resilience in late adolescence and risk of smoking, high alcohol consumption and drug use later in life. J Epidemiol Community Health, 73(6), 496-501.

Kotlyar, M., Thuras, P., Hatsukami, D. K., & Al’Absi, M. (2017). Sex differences in the physiological response to the combination of stress and smoking. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 118, 1-12. Web.

Kwako, L. E., & Koob, G. F. (2017). Neuroclinical framework for the role of stress in addiction. Chronic Stress, 1, 1-14. Web.

Lasser, K., Boyd, J.W., Woolhandler, S., Himmelstein, D.U., McCormick, D., Bor, D. H. (2000). Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 28420, 2606–2610.

Lawless, M. H., Harrison, K. A., Grandits, G. A., Eberly, L. E., & Allen, S. S. (2015). Perceived stress and smoking-related behaviors and symptomatology in male and female smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 51, 80-83. Web.

Lawrence, D., Mitrou, F., Zubrick, S. R. (2005). Non-specific psychological distress, smoking status and smoking cessation: United States National Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health.

Lawrence, D., Williams, J. M. (2016). Trends in Smoking Rates by Level of Psychological Distress—Time Series Analysis of US National Health Interview Survey Data 1997–2014, Nicotine & Tobacco Research 18 (6), 1463–1470. Web.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer.

Mansouri, A., Kavi, E., Ahmadpoori, S.F., Amin, E., Bazrafshan, M.R., Piroozi, A., Jokar, M. and Zare, F., 2019. Cigarette Smoking and Coping Strategies with Stress in Young Adults of Larestan. Jundishapur Journal of Health Sciences, 11(1).

Mauro, P. M., Canham, S. L., Martins, S. S., & Spira, A. P. (2015). Substance-use coping and self-rated health among US middle-aged and older adults. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 1-13. Web.

McClave, A. K., Dube, S. R., Strine, T. W., Kroenke, K., Caraballo, R. S., Mokdad, A.H. (2009). Associations between smoking cessation and anxiety and depression among U.S. adults. Addict Behav, 346. 491–497.

Morel, C., Fernandez, S. P., Pantouli, F., Meye, F. J., Marti, F., Tolu, S.,… & Moretti, M. (2018). Nicotinic receptors mediate stress-nicotine detrimental interplay via dopamine cells’ activity. Molecular psychiatry, 23(7), 1597-1605.

Morris, M. C., Mielock, A. S., & Rao, U. (2016). Salivary stress biomarkers of recent nicotine use and dependence. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 42(6), 640-648.

McBride, D. M. (2020). The process of research in psychology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Nardi, P. M. (2018). Doing survey research: A guide to quantitative methods (4th ed.). Routledge.

Nestor, P. G., & Schutt, R. K. (2018). Research methods in psychology: Investigating human behavior (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Ostroumov, A., & Dani, J. A. (2018). Convergent neuronal plasticity and metaplasticity mechanisms of stress, nicotine, and alcohol. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 58, 547-566.

Parrott, A. C. (1999). Does cigarette smoking cause stress?American Psychologist, 54(10), 817.

Percy, W. H., Kostere, K., & Kostere, S. (2015). Generic qualitative research in psychology. The Qualitative Report, 20(2), 76-85. Web.

Perkins, K. A., Ciccocioppo, M., Conklin, C. A., Milanak, M. E., Grottenthaler, A., Sayette, M. A. (2008). Mood influences on acute smoking responses are independent of nicotine intake and dose expectancy. J Abnorm Psychol. 117(1), 79-93. Web.

Pina, J. A., Namba, M. D., Leyrer-Jackson, J. M., Cabrera-Brown, G., & Gipson, C. D. (2018). Social influences on nicotine-related behaviors. International Review of Neurobiology, 140, 1-32. Web.

Pomerleau, C. S., & Pomerleau, O. F. (1987). The effects of a psychological stressor on cigarette smoking and subsequent behavioral and physiological responses. Psychophysiology, 24(3), 278-285.

Reid, H. H., & Ledgerwood, D. M. (2015). Depressive symptoms affect changes in nicotine withdrawal and smoking urges throughout smoking cessation treatment: Preliminary results. Addiction Research & Theory, 24(1), 48-53.

Robles, T. F. (2019). Health, stress, and coping. In E. J. Finkel & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Advanced social psychology: The state of the science (2nd ed., pp. 431-452). Oxford University Press.

Rooney, B. J., & Evans, A. N. (2018). Methods in psychological research (4th ed). SAGE Publications.

Rudolph, A. E., Bazzi, A. R., & Fish, S. (2016). Ethical considerations and potential threats to validity for three methods commonly used to collect geographic information in studies among people who use drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 84-90. Web.

Schmidt, A. M. (2017). Psychological Health and Smoking in Young Adulthood: Smoking Trajectories and Responsiveness to State Cigarette Excise Taxes. The University of North Carolina

Siegel, A., Korbman, M. and Erblich, J., 2017. Direct and Indirect Effects of Psychological Distress on Stress-Induced Smoking. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 78(6), pp.930-937.

Steuber, T. L., Danner, F. (2006). Adolescent smoking and depression: Which comes first? Addictive Behaviours. 31(1), 133-136. Web.

Stubbs, B., Veronese, N., Vancampfort, D., Prina, A.M., Lin, P.-Y., Tseng, P.-T., Evangelou,E., Solmi, M., Kohler,C., Carvalho, A.F., & Koyanago, A. (2017). Perceived stress and smoking across 41 countries: A global perspective across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Scientific Reports, 7, 7597. Web.

Sun, B., VanderWeele, T. and Tchetgen Tchetgen, E.J., 2017. A multinomial regression approach to model outcome heterogeneity. American journal of epidemiology, 186(9), 1097-1103.

Tavolacci, M. P., Ladner, J., Grigioni, S., Richard, L., Villet, H., & Dechelotte, P., (2013). Prevalence and Association of Perceived Stress, Substance Use and Behavioral Addictions: A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Students in France, 2009-2011. BMC Public Health 13, 724. Web.

The British Psychological Society. (2014). Code of Human Research Ethics. Web.

The British Psychological Society. (2017). Ethics guidelines for Internet-mediated research. Web.

Thomeer, M. B., Hernandez, E., Umberson, D., & Thomas, P. A. (2019). Influence of social connections on smoking behavior across the life course. Advances in Life Course Research, 42, 100-294.

Torres, O. V., & O’Dell, L. E. (2016). Stress is a principal factor that promotes tobacco use in females. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 65, 260-268. Web.

Varnhagen, C., Gushta, M., Daniels, J., Peters, T., Parmar, N., Law, D., Hirsch, R., Takach, B., & Johnson, T., (2005). How Informed Is Online Informed Consent? Ethics & Behavior. 15. 37-48. Web.

Wildemuth, B.M. ed., 2016. Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science. ABC-CLIO.

Wiggert, N., Wilhelm, F. H., Nakajima, M., & Al’Absi, M. (2016). Chronic smoking, trait anxiety, and the physiological response to stress. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(12), 1-18. Web.

Zikmund, W.G., Carr, J.C. and Griffin, M., 2013. Business Research Methods. Cengage Learning.

Zhou, S., Willison, C., & Jarman, H. (2019, November). Smoking and mental health among college students: Reconceptualizing tobacco control policies. In APHA’s 2019 Annual Meeting and Expo (Nov. 2-Nov. 6). American Public Health Association.