Abstract

This paper presents an attempt to examine frontotemporal dementia (FTD) based on a critical review of the evidence-based literature. Considering that many patients under the age of 65 and over face mental issues, this topic cannot be underestimated. To better understand the identified disease, the paper provides an analysis of its prevalence, genetic risks, and other factors that can affect its onset. Furthermore, the paper analyzes behavioral and cognitive symptoms, such as personality problems, memory issues, language difficulties, and a lack of social tact. While discussing FTD, it is also important to distinguish it from other diseases with similar symptoms, including some neurodegenerative illnesses, such as Alzheimer’s disease and non-degenerative processes. The paper also focuses on a range of treatment options to clarify effective drugs and those that were not useful. Several visual instruments, namely tables and figures, provide more information on the subjects discussed.

Introduction

Behavior and cognitive functioning largely determine a person’s quality of life. When some neurodegenerative conditions appear in the human brain, it leads to problems with communication, relationships, and self-awareness. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), also known as frontotemporal lobar degeneration, is a neurodegenerative disease that affects either the temporal or frontal lobes or both. It is the second most common dementia with an early onset, which is manifested by speech and behavioral disorders (Leroy et al., 2021). This paper aims to research FTD, focusing on its prevalence, genetic risks, as well as cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Based on the analysis of evidence-based sources, it is expected to identify the existing diagnostic criteria and determine available treatment options.

Prevalence and Genetic Risks

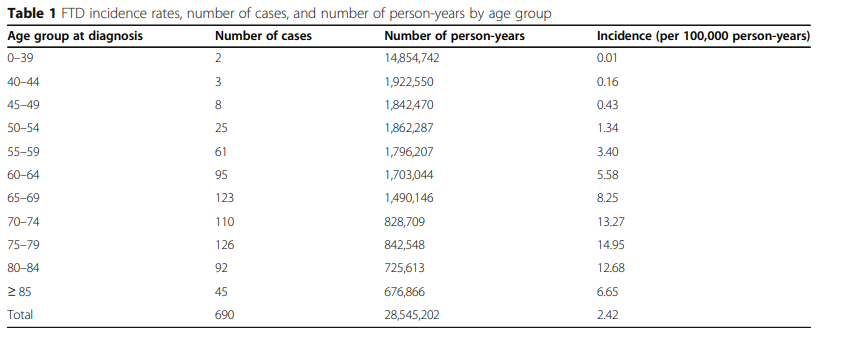

FTD unifies several forms of neurodegenerative diseases that have common symptoms. In a recent study, Leroy et al. (2021) state that “FTD cases have been found to account for 1.6 to 7% of dementia cases” (p. 2). The mentioned author also clarifies that “FTD prevalence was estimated between 0.01–4.61 per 1000 person and the incidence between 0.01–2.5 per 1000 person/year (Leroy et al., 2021, p. 2). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the rate of dementia is doubling every 20 years, and it may reach 115.4 million in 2050 (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). It should be stressed that the given disease is often underdiagnosed since many patients do not accept their cognitive impairment. Therefore, there is a need to share data about FTD, which is critical to improving its recognition. Table 1 presents detailed information about the results of the study in a regional memory clinic network, which analyzed data from 690 patients with FTD. This table clearly shows the age of the disease onset in the patients involved in the study.

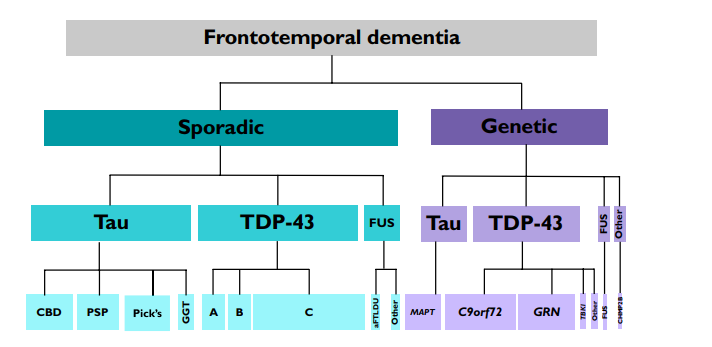

The research shows that many mutations in several different genes lead to the development of numerous subtypes of frontotemporal dementia. In some cases, microscopic intracellular pathological structures containing tau protein, also known as Pick bodies, are found in the affected parts of the brain (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). Earlier, FTD was defined as Pick’s disease, but now this term is used only to refer to one of the subtypes of dementia in which Pick’s bodies are found (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). Another form of frontotemporal lobar degeneration appears under the impact of TDP-43 protein (Figure 1). The publications on the prevalence of dementia in patients under 65 years of age show that the main cause of dementia in presenile age is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is followed by vascular dementia (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). However, more than half of people with this condition do not have a family history of the disease.

In addition to genetic risks, one should mention a range of factors that are taken into account while examining FTD cases. Prusiner, a professor of neurology and biochemistry, theorizes that several factors may directly affect the occurrence and development of dementia (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). The first reason is prion-like characteristics that evoke a type of infectious pathogens contained in brain cells. Cognitive disorders (for example, the deterioration in the quality of mental activity or memory loss) may also serve as the triggering points for the occurrence of FTD. Aphasia is a disorder associated with a violation of the speech apparatus that may serve as both the triggering issue and a result of dementia (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). In addition, infectious lesions, eating disorders, chronic alcoholism, and brain injury promote the development of FTD.

Cognitive and Behavioral Symptoms

Signs and symptoms can vary significantly from one patient to another. Nevertheless, researchers have identified several groups of symptoms that tend to occur and are dominant in subgroups of people with this disorder. In general, the symptoms of frontotemporal dementia progress over time, and this process takes several years (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). Ultimately, a patient completely ceases to manage herself or himself and begins to need round-the-clock monitoring and care.

The behavioral symptoms of FTD include certain changes in one’s mood and personality. Often, it is possible to note the signs of unwillingness to talk with not only colleagues but also family members. According to Leroy et al. (2021), a lack of social tact and obsessive behaviors may also signalize the onset of the given disease. More to the point, a lack of judgment, empathy and personal hygiene should also serve as alarming issues while diagnosing a patient. Impaired self-monitoring, deteriorating eating habits, and compulsive ideas of putting hands in one’s mouth can also be found in the literature that examines behavioral symptoms of FTD (Leroy et al., 2021). Therefore, it is possible to suggest that patients usually cannot independently identify their symptoms, which means that they need certain assistance to attend care facilities and receive appropriate treatment.

Cognitive decline is a key sign of frontotemporal dementia, which includes a wide range of symptoms. Moreover, Greaves and Rohrer (2019) emphasize that “neuropsychometric measures are abnormal in presymptomatic carriers around 5 years prior to expected symptom onset” (p. 2077). Speech disorders can sometimes be the first symptoms of FTD, which in such cases begins as primary progressive aphasia. However, in many cases, speech disorders develop simultaneously with deregulatory and behavioral disorders (Ducharme et al., 2020). For FTD, speech disorders are most characteristic in the form of progressive dynamic and/or amnestic aphasia, which progresses up to the complete disappearance of spontaneous speech activity. The development of progressive, dynamic aphasia appears when the left frontal lobe of the brain is damaged. Ducharme et al. (2020) stress that verbs disappear from the spontaneous speech of patients. The speech of patients reduces to monosyllabic answers to the question posed, and spontaneous speech becomes limited.

The predominant lesion of the left temporal lobe leads to the clinical manifestations of speech disorders that correspond to the picture of amnestic aphasia. Ducharme et al. (2020) assume that the earliest symptom of this type of FTD includes difficulties in naming objects. The problems with using and recognizing written and/or oral speech are prevalent. For example, patients experience issues with remembering a word, which leads to using “it” to name objects. Word meanings become less important for people with FTD, which causes mistakes in communication (Greaves & Rohrer, 2019). In addition to language problems, thought problems should also be noted since they are directly related to one’s ability to interact with others. As an example, the fluency and grammatical structure of the patient’s speech are not disturbed, but it becomes devoid of content due to the absence of nouns.

Potential Differential Diagnoses and Diagnostic Criteria

Speaking about the diagnostics of frontotemporal dementia among patients under 55 and over, it is critical to distinguish it from non-degenerative processes and other neurodegenerative illnesses. Namely, cerebrovascular disease, primary psychiatric illness, and tumors may evoke the behavioral symptoms identified in this paper’s previous section (Leroy et al., 2021). As for neurodegenerative conditions that should be separated, there are some atypical forms of Alzheimer’s disease.

While differentiating diagnosis can be challenging, it is recommended for care providers to focus on the extent of atrophic changes in a certain patient. In this case, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful for detecting changes in the brain (Leroy et al., 2021). It should be stressed that a range of diagnostic tools is critical to properly assess patients’ cases. However, it has been shown that visual assessment of MRI data may not be enough to identify the characteristic pattern of brain atrophy. According to some studies, its diagnostic accuracy in detecting FTD is about 65% (Panza et al., 2020). One of the ways to improve the objectivity of MRI examination is voxel-oriented morphometry (VOM), in which the zones of significant atrophy of gray matter are revealed by the comparison of the volume of two given groups.

Genetic testing is another method to distinguish between FTD and similar diseases. Since there is a diagnostic overlap of the behavioral variant with other clinical types of FTD, it becomes important to establish the subtypes of protein pathology, such as tau-positive or ubiquitin-positive (Panza et al., 2020). It is significant to keep in mind that it is sometimes difficult to determine the so-called pathogenicity of variants since some individuals are carriers of two mutations. Moreover, the patients with the same mutation may present different phenotypes at different times (Panza et al., 2020). It is expected that the next generation of sequencing will allow all genes to be examined simultaneously. Today, individuals with the symptoms or risk of disease can be examined in centers of expertise as part of genetic counseling.

The diagnosis of the disease relies primarily on clinical manifestations and neuroimaging patterns. At the same time, the positron emission tomography (PET) scan is useful for differential diagnosis of mental illness, mainly to detect AD. As Ducharme et al. (2020) noted, amyloid ligand PET is licensed but not widely available; tau neuroimaging is also in the experimental stage. In turn, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing may help differentiate between FTD and AD, but an elevated tau level is not a definitive marker (Ducharme et al., 2020). In turn, Leroy et al. (2021) emphasize that FTD remains underdiagnosed since it often takes a long time before conducting necessary testing.

Treatment Options

A thorough review of the available evidence-based literature shows that there is no specific treatment for frontotemporal dementia that can be used to cure patients (Trieu et al., 2020). However, it is possible to provide mostly supportive measures to ensure appropriate life quality. For example, the environment of a person with FTD should be bright and familiar, and it should aim to reinforce his or her orientation and maintain cognitive abilities (Panza et al., 2020). Patient safety measures should also be implemented, such as establishing signal monitoring systems for patients who may stray.

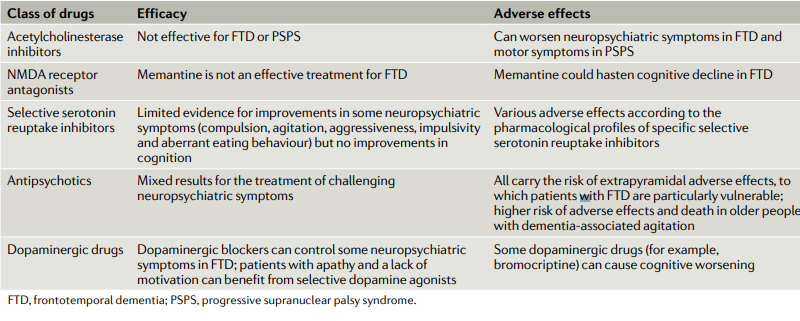

Available drugs for the treatment of FTD have been developed for the treatment of AD, and most of them affect various neurotransmitter systems that are impaired by the disease. The studies conducted on the therapy of FTD are limited to a small number of patients and have an open design (Trieu et al., 2020). In a number of cases, initially, promising drugs failed to prove their effectiveness in more rigorous randomized and placebo-controlled trials. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChE) are among the main drugs for the treatment of AD and have been widely studied in FTD, but the analysis of the trials was disappointing (Table. 2). Current results suggest that AChE inhibitors are ineffective in patients with FTD and may adversely affect behavioral symptoms and motor function (Panza et al., 2020). The mentioned authors state that further research is necessary to better understand the impact and potential adverse effects of AChE inhibitors.

The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA) receptor agonists compose another category of drugs for FTD patients. For example, memantine was investigated in both open-label and randomized, placebo-controlled randomized trials. Their results did not demonstrate a significant improvement in behavioral symptoms and changes in the overall clinical impression (Trieu et al., 2020). In open studies, memantine at a dose of 20 mg per was shown to improve behavioral and psychopathological symptoms such as anxiety, apathy, depression, and disinhibition, especially at the stage of moderate and severe dementia (Trieu et al., 2020). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small number of patients participating in the study.

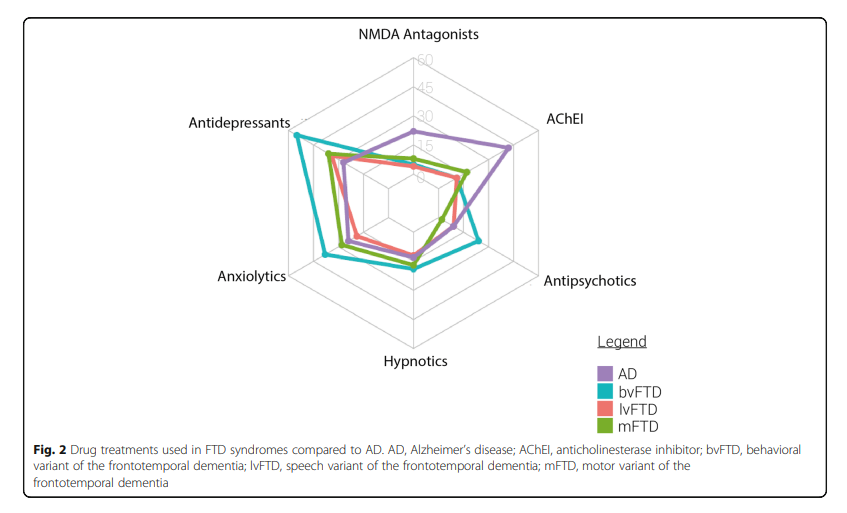

In some cases of FTD, a clear dopaminergic deficit was revealed with a decrease in the level of dopamine metabolites, as well as in the number of presynaptic receptors. Therefore the potential effectiveness of dopaminergic therapy (primarily small doses of levodopa, to a lesser extent – dopamine agonists receptors or amantadine) (Leroy et al., 2021) (Figure 2). Outside of the Parkinsonian syndrome, the effect of this group of drugs has not been studied in controlled studies, although some improvement in cognitive and behavioral areas has been noted in small open studies (Leroy et al., 2021). To correct severe behavioral symptoms, including excitation, aggression, and psychosis, it is recommended to resort to the use of antipsychotics. However, no controlled efficacy studies have been conducted on FTD antipsychotics, although a positive effect of risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole has been described (in small groups of patients) (Panza et al., 2020). At the same time, the neuroleptic should be used with caution and in minimal doses, considering the tendency of patients to develop parkinsonism. In this connection, it is preferable to use atypical antipsychotics. The symptomatic pharmacotherapy of FTD is summarized in Table. 2.

Since the disease will steadily progress, it is necessary to find a person who will care for the person with FTD, helping him or her in daily life, taking care of his or her safety, and providing transportation and help with financial matters (Trieu et al., 2021). The attending physician should discuss lifestyle changes with the patient, for example, when it may be necessary to stop driving. Regular aerobic exercise can improve the patient’s mood and positively affect his or her thinking. Some studies have shown that aromatherapy, pet therapy, and music therapy can be beneficial for people with this form of dementia (Leroy et al., 2021). As the ability to think and speak steadily worsens in patients with FTD, it may be necessary to appoint a family member, guardian, or attorney to manage financial and other affairs.

Conclusion

To conclude, determining exactly which dysfunctions fall into the category of FTD presents a particular challenge for researchers. A wide range of cognitive and behavioral symptoms includes apathy, reduced self-awareness, personality problems, disorientation, and language issues. While FTD refers to non-curable diseases, the treatment of symptoms is carried out as needed. Most therapeutic strategies for FTD aim at improving behavioral or cognitive symptoms. While the routine use of AChE inhibitors and memantine in FTD did not prove to be effective, dopaminergic drugs and antipsychotics can be recommended to support patients’ quality of life by managing their symptoms.

References

Ducharme, S., Dols, A., Laforce, R., Devenney, E., Kumfor, F., Van Den Stock, J., & Pijnenburg, Y. (2020). Recommendations to distinguish behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia from psychiatric disorders. Brain, 143(6), 1632-1650.

Greaves, C. V., & Rohrer, J. D. (2019). An update on genetic frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Neurology, 266(8), 2075-2086.

Leroy, M., Bertoux, M., Skrobala, E., Mode, E., Adnet-Bonte, C., Le Ber, I., & Lebouvier, T. (2021). Characteristics and progression of patients with frontotemporal dementia in a regional memory clinic network. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 13(1), 1-11.

Panza, F., Lozupone, M., Seripa, D., Daniele, A., Watling, M., Giannelli, G., & Imbimbo, B. P. (2020). Development of disease-modifying drugs for frontotemporal dementia spectrum disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology, 16(4), 213-228.

Trieu, C., Gossink, F., Stek, M. L., Scheltens, P., Pijnenburg, Y. A., & Dols, A. (2020). Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: A systematic review. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 33(1), 1-15.